The DC Universe is asleep right now.

This is not a commentary on the state of their cinematic universe. I’m talking about the good ol’ comic book DCU, which is in the second half of their two-month Knight Terrors event. A new villain calling himself Insomnia wants to get his hands on the Nightmare Stone, a powerful artifact that used to belong to the Justice League’s old enemy Dr. Destiny. Insomnia believes that Doc Dee has hidden the stone inside the dreams of somebody in the DCU, so he’s made everyone on Earth fall asleep, allowing him to search for it. It’s been an interesting story, diving into the dreams of DC’s greatest heroes and villains and getting a taste of their worst fears. (You should see what the Joker is afraid of.) Most importantly, though, Knight Terrors is the latest iteration of that thing that we comic book nerds both adore and fear: the crossover event.

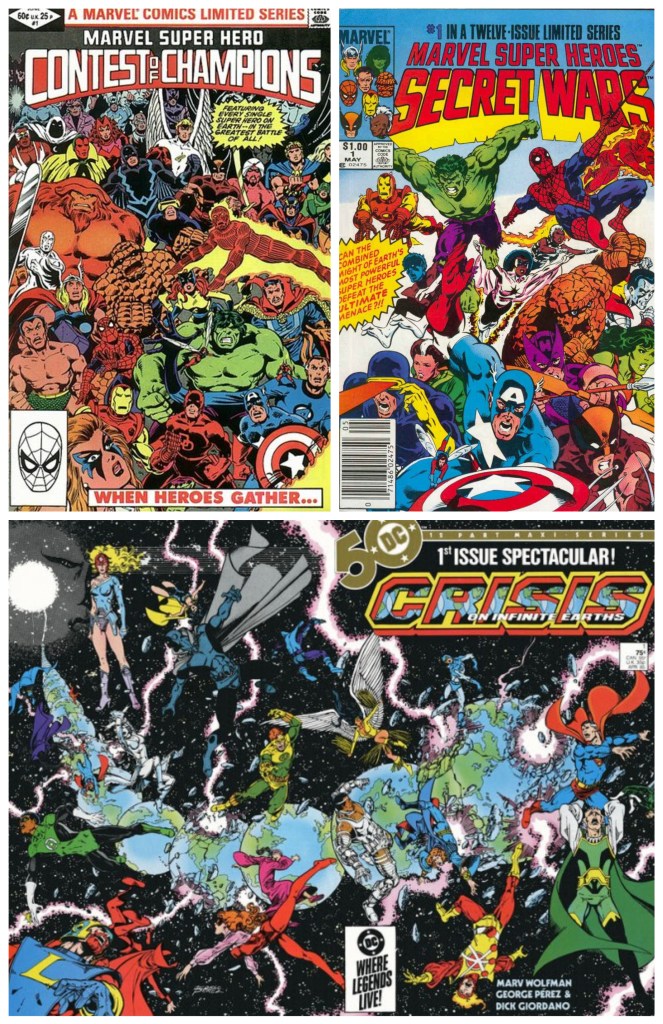

Most comic historians will agree that the “shared universe” conceit, in which most or all of the characters published by the same company are said to co-exist, can be traced back to 1940 and the first appearance of the Justice Society of America in All-Star Comics #3. In the early days, the JSA was little more than a framing device, in which the heroes would gather around a table and tell each other tales of their exploits, but eventually the stories would evolve to the point where they were having adventures together. Guest appearances in each other’s books became common, more teams were formed, and eventually both Marvel and DC Comics had sprawling worlds of interconnected characters. In a way, it’s baffling that it took 42 years for the next logical step in storytelling to happen: mashing everybody in the universe into a single story. That story was 1982’s Contest of Champions, a three-issue miniseries in which the Marvel Comics all-stars were abducted by a couple of the Elders of the Universe and forced to battle each other. It was a completely self-contained story that didn’t touch on any other book, but it was considered a precursor for the next step: the 12-issue Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars in 1984. This time, we saw many of the Marvel heroes – in their own titles – encounter a mysterious device that whisked them away to parts unknown. They returned in the next issue after an absence of some weeks, many of them with changes. The maxiseries told the story of what happened to them in-between those two points.

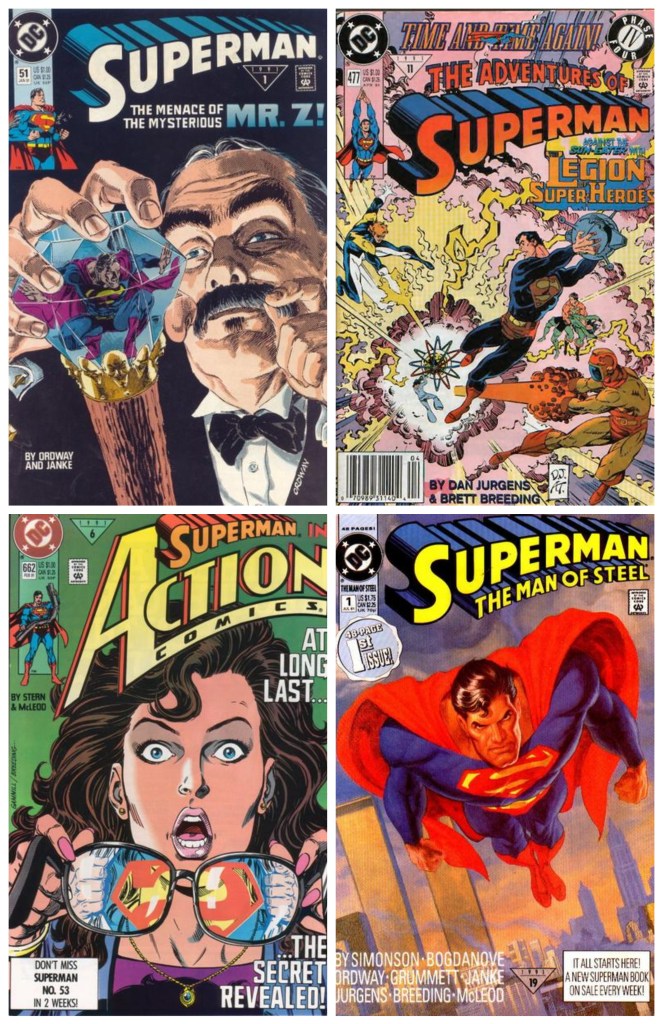

DC got into the game in 1985 with Crisis on Infinite Earths, and that’s when things really got wild. Contest of Champions and Secret Wars were both relatively self-contained stories. Although Secret Wars had repercussions for the regular series of the assorted characters (Spider-Man’s black costume, which would eventually become Venom; She-Hulk leaving the Avengers for the Fantastic Four; etc.) the story itself stayed in those 12 issues. In Crisis on Infinite Earths, for the first time, the story spilled out into the other comics being published by DC. While the heroes of the multiverse struggled to keep it together in the main series, most of the other books published by the company had side-stories that showed how the stars of that title were dealing with the collapse of reality. Green Lantern dealt with the destruction of an entire sector of space, DC Comics Presents booted Superman to an alternate reality where he met a young version of himself, and in Wonder Woman’s title she joined with the gods of Olympus to protect her home.

Since then, the crossover has evolved again and again, with different forms that each have their own pros and cons. In some cases, a story in a single title or family of titles grew big enough that it only made sense to show the effects on other books. In Marvel’s Inferno (1989), the X-Men family of comics told the story of a demonic invasion of New York, and since most of Marvel’s heroes lived in New York it only made sense to show how Spider-Man, the Avengers, and the Fantastic Four were dealing with it as well. Later that same year we got Acts of Vengeance, a story wherein Loki plotted to destroy the Avengers by manipulating the Marvel Universe’s villains into attacking different heroes than those they usually fought. Yeah, I’m not entirely sure how that was supposed to work either, but it was a fun story: Spider-Man dealt with the X-Men’s enemy Magneto, while Daredevil’s foe Typhoid Mary set her sights on the Power Pack, and so forth. These kinds of crossovers work out fairly well, as it’s easy for readers to ignore any titles they don’t want to read. On the other hand, if they aren’t reading the core titles in which the story is taking place, they may be confused as to what is going on.

However, from a company standpoint, there’s one major problem with crossovers like that: there’s no extra books being sold. So the next level of crossover has a main miniseries, with stories touching on the heroes across the DCU. After the original Crisis, DC made this an almost-annual format for many years, with the likes of Legends, Millennium, Invasion!, Final Night, Genesis, and Underworld Unleashed all following suit. Marvel did it several times as well, with Secret Wars II, Infinity Gauntlet, and its assorted sequels. This is the kind of crossover I grew up with, and in many ways it’s still my favorite. The fact that it touches on the ongoing comics gives the story weight and makes it feel like it “matters” more than if the book is totally self-contained, and for the most part, you still only have to read the main title and any crossovers that you want, pushing aside those that you don’t.

Later crossovers like Civil War and Fear Itself would expand on this concept: the main miniseries, crossovers into the ongoing books, and assorted miniseries and one-shots that spin off of the main book. This expands the story and allows the storytellers to touch on more elements of the event, and of course, it gives the publisher more books they can potentially sell. Publishers love that. Sometimes they love it so much that they’ll do a spinoff miniseries even if the characters involved currently have an ongoing. There are 97 X-Men titles at any given time, so was it strictly necessary to do a three-issue World War Hulk: X-Men miniseries instead of just putting the story in one of those? I say thee nay.

Then there’s the tier that we’re seeing more often these days, in which the crossover doesn’t touch the ongoing titles at all, but only features spinoffs and one-shots. There are, I think, two reasons this happens.

1: Money.

2: Writers.

I don’t think the first point needs much of an explanation, but let me tell you what I mean by the second one. The comic book industry has become increasingly writer-focused over the years, and while in many ways that’s a good thing, that does come with a degree of compartmentalization. Whereas in the past, editors would call up the writer of New Warriors and tell him to link his book to Infinity War whether he wanted to or not, today there’s more of a reluctance to disrupt the ongoing story. Al Ewing’s fantastic Immortal Hulk series was an excellent horror story that is perfect for binge-reading now that it’s over. But if you’re reading that story in a collected edition years later, it would be somewhat disconcerting to suddenly stop to deal with an invasion of symbiotes spilling over from the Spider-Man comics. So instead, there were Immortal Hulk one-shot specials when the title dealt with the events of the Absolute Carnage and King in Black crossovers, and the main book went unmolested.

The benefit of this is that the crossover doesn’t impact the story when you’re reading it in a vacuum. There are two cons that come to mind, though. First, if a crossover is entirely self-contained, it’s easy to ignore it and decide it’s inconsequential to the meta-story of the shared universe as a whole. Second, it has a tendency to cause the main story to spill out into the spinoffs in a way that doesn’t happen as often with the other kinds of crossovers. Grant Morrison’s Final Crisis was a bit of a mindbender to begin with, but the ending is COMPLETELY out of the blue if you didn’t choose to read the Final Crisis: Superman Beyond two-issue miniseries that accompanied it.

A story like Knight Terrors is a relatively new variant on this format. The crossover is told entirely through crossover miniseries, but those miniseries are replacing the ongoing comics for the duration of the event. Instead of following June’s Nightwing #105 with July’s Nightwing #106, July and August give us Knight Terrors: Nightwing #1 and #2, with #106 saved for September. This is, by my count, the third time DC has done this, the previous times being Convergence in 2015 and Future State in 2021. It’s nice, in that it doesn’t disrupt the main book at all, but it also has a habit of making the event itself feel rather inconsequential. (Future State in particular has largely faded into irrelevance in the DCU.)

Up until now, I’ve really only talked about format. I’m not making value judgments on any of these stories: there are both good and bad examples of every kind of crossover. What matters, I think, is what exactly you’re trying to accomplish with the story. Are you “just” telling a big story? Well, the first format I discussed is probably the right one. We mostly see that now with smaller crossovers, things like the Sinestro Corps War that only impacted the Green Lantern books (plus one issue of Blue Beetle). But even those “smaller” crossovers are starting to go the route of having one-shots or miniseries spinoffs: the upcoming Gotham War storyline will feature in the Batman and Catwoman ongoing titles but also have a few one-shots and a miniseries focusing on Jason Todd.

Sometimes publishers label books as part of a crossover no matter how inconsequential they are, and that can irritate readers. People who picked up the Crisis on Infinite Earths issues of Swamp Thing were rightly irritated that the only connection seemed to be the skies turning red. Even when the book is objectively entertaining, it’s a bit frustrating. Geoff Johns and the late George Perez did a magnificent job on Final Crisis: Legion of Three Worlds (I would even argue that, to date, it was the LAST great Legion of Super-Heroes story), but pretending it had great significance to the Final Crisis storyline was something of a stretch.

Sometimes these crossovers are intended to reset things: DC has done that with Flashpoint and Dark Crisis on Infinite Earths, which led to the New 52 and Dawn of DC reboots, respectively. Sometimes these are intended not to re-set, but to set things up in the first place. That’s what the nascent Valiant Comics did in 1991 with Unity. When their universe was still young they tied together their six existing titles (four of which were less than a year old), launched two new titles, and introduced new characters and concepts that in turn would develop into more titles in the next year. It was a huge success and Valiant was the hot ticket, becoming so successful that only a few years later Acclaim bought the company and promptly ran it into the ground.

People like to complain about “event fatigue” in comics the same way that many of them complain about “superhero fatigue” in movies, but the fact that people keep buying these books seems to indicate that they aren’t that exhausted. And as always, quality matters. People rarely complain about “too many comics” if they actually like the stories that they’re reading – it’s only when following a story gets to be a chore that they go to the internet and gripe. I don’t think crossovers are going anywhere, and honestly, I don’t really want them to. So I guess the important thing when planning them out, publishers, is to think really hard before you get into these storylines, and ask your doctor (Strange, not Doom) what kind of crossover is right for you.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His current writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, a new episode of which is available every Wednesday on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform. He knows that there are a LOT of crossover events he didn’t mention in this column, so before you reply with, “Hey, you forgot XYZ,” know that he didn’t. He just didn’t have room to make this comprehensive. Cut him some slack.