I think the movie Holes is pretty good.

I know, it’s unusual for me to kick off one of these columns with something so overtly political, but bear with me here.

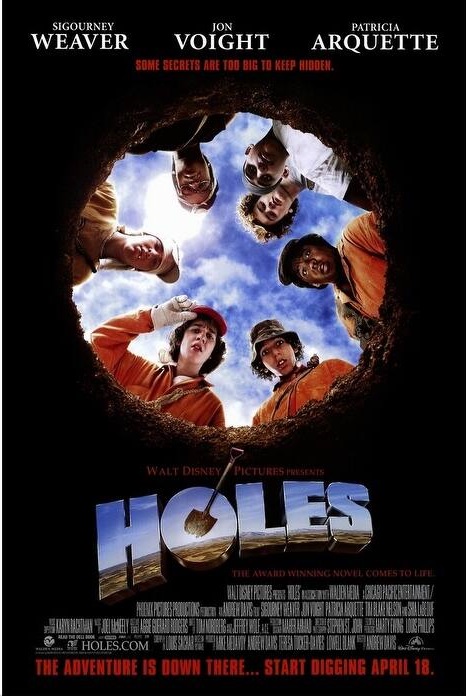

Holes, which came out in 2003, is an adaptation of Louis Sachar’s young adult novel of the same name. The story is about a kid named Stanley Yelnats who is falsely accused of stealing a pair of very expensive celebrity shoes from a charity auction and sentenced to 18 months at a juvenile detention facility called Camp Green Lake. As it turns out there’s nothing green about the camp, nor is there a lake there anymore – just the desert remains of a dried lakebed where the detainees are forced to dig five-foot holes day after day in an effort to “build their character.” The film bounces around three different timelines: Stanley’s story is intercut with that of his great-great-grandfather, who accidentally brought a curse down on five generations of his family, and the origin story of a brutal outlaw named “Kissin’” Kate Barlow, who terrorized the Green Lake community a century ago.

I remembered enjoying the movie when it first came out, but a few days ago I watched it for the first time in several years and I was really impressed by how tightly plotted the film is. Even with juggling three timelines there is virtually no fat in the plot. Everything in the story turns out to be significant in the end, either to revealing the truth about the two timelines that take place in the past or to bringing the storyline of the present day to a satisfying conclusion. It’s a really good movie, and I’m not even kidding when I say that screenwriters could do worse than to study it when it comes to learning how to put a story together.

Part of the reason for the tightness of the story, I think, is because the screenplay was written by Louis Sachar himself, adapting his own novel. True, sometimes when this happens the original writer can be a tad too precious about keeping their favorite bits or not understand the necessities of adaptation, but Sachar did a stellar job. However, as I often do when I watch a movie I really enjoy, I spent a little time online afterwards looking into the history of the film and learned something I hadn’t known before: Sachar’s script was NOT the first attempt to adapt the book. The first attempt at adapting the story was written by Richard Kelly, who is probably best known as the writer and director of Donnie Darko, which film scholars among you will recognize as being one of the last movies one would think about when drawing comparisons to Holes. Furthermore, that Kelly script – as it turns out – is freely available online, and I clicked on it to take a look.

Kelly’s version begins with a narrator described as an “elderly voice” saying – and I swear, I am transcribing this verbatim: “Once…when it was still early in the twenty-first century…there existed a prison in a sea of sand.”

Holy crap.

It continues.

“All signs of life in this place had been destroyed by something terrible…and that something had dried up into the earth…and the earth was a prison for all mankind.”

HOLY.

CRAP.

Had Kelly even read the book?

Incidentally, the ellipses you’re seeing in these passages were there originally, I didn’t omit anything. This is HOW IT IS WRITTEN.

At this point I saved the link so I could go back and read it later, because something this completely bonkers has to be examined slowly, carefully. When Stanley “Kramer” shows up later on the page, the narrator continues by telling us “He did not feel sorry for what he had done…but feeling sorrow is not adequate punishment for such a crime. Feeling sorrow does not absolve the crime from the memory of the victims…if the victims are still breathing.”

Was Kelly even aware of the fact that there is a book?

Adaptations are not a new art form, guys. The Greeks borrowed from existing myths and legends when they invented modern theater. Virtually all of Shakespeare’s most famous plays are based on history, mythology, or earlier poetry that he expanded in his own way. The Lego Movie was based on the works of Eudora Welty. So it’s not that I have any objection to adapting a work from one medium to another. But at SOME point, it seems like someone has to ask the question: if I’m changing the story this much, is it even still really an adaptation?

Change is inevitable when changing from one medium to another, and for any of a thousand reasons. In The Hunger Games, for instance, the novel is written from the first-person point of view of Katniss Everdeen and is heavily loaded with her internal monologue. This is difficult to do well in a movie, and thus the information we learn in monologue – whether it’s plot-driven or character-driven – has to be imparted to the audience in a different way. Sometimes the changes are pragmatic. Back to Holes for a moment – in the novel, Stanley begins the story as a fat boy who gradually loses weight due to the physical labor he’s forced to undergo. The filmmakers decided to drop this and cast the relatively slim Shia LaBoeuf under the reasoning that it would be too difficult to make a 14-year-old actor gain and lose weight so drastically over the course of filming, not to mention potentially dangerous to his health. That is a 100 percent acceptable change.

Sometimes changes are just a matter of understanding what the audience can handle. I’ll give you two examples from Stephen King. Cujo is a book about a mother and her child trapped in an increasingly hot car by a violent and rabid St. Bernard. In the book – spoiler alert here for a 43-year-old novel – the child dies of heatstroke. But in the movie, the filmmakers let the kid live, thinking his death would be too much for the audience. There’s a similar change in the film version of Misery, about a writer who gets in a terrible car accident and is rescued by his “biggest fan,” who turns out to be a deranged lunatic. In the book, to prevent Paul Sheldon from escaping, the insane Annie Wilkes cuts off his feet. If that sentence shocked you it’s probably because you are more familiar with the famous scene in the movie, where she “only” hobbles him by breaking his ankles with a sledgehammer. Reportedly, the producers felt like audiences would never forgive the actress, Kathy Bates, if she went so far as to actually cut his feet off. And if you think that audiences are smart enough to know the difference between the actor and the behavior of their character, look up the way “fans” treated Anna Gunn for the things Skyler White did on Breaking Bad.

When it comes to these changes, the filmmakers chose to lessen the tragedy of the book. I don’t think that we’re saying that book readers are more accepting of gore or death than people who watch movies, though. I think the lesson here is that it is more difficult – more disturbing – to watch certain tragedies than to read about them. On the other hand, there’s the adaptation of King’s novella The Mist, which is a book with an ambiguous ending. The film, however, goes in the OPPOSITE direction, making the ending OVERTLY tragic. In this case, though, making the ending far worse than the original actually works. Stephen King himself has reportedly said he prefers the ending of the movie to the that of the story he wrote.

Time is also a big factor when it comes to adaptation. If you’re adapting a doorstopper novel, especially into a film intended for theatrical distribution, it’s virtually impossible to squeeze in everything. Lord of the Rings fans have elevated the absence of Tom Bombadil from the film version of the beloved trilogy to meme status. To a lesser degree, the same is true for the Scouring of the Shire. As much as I appreciate those sequences in the book, though, when we’re talking about movies that already have a running time that’s longer than the first marriages of certain people I went to college with, I can forgive Peter Jackson for laying those pieces aside.

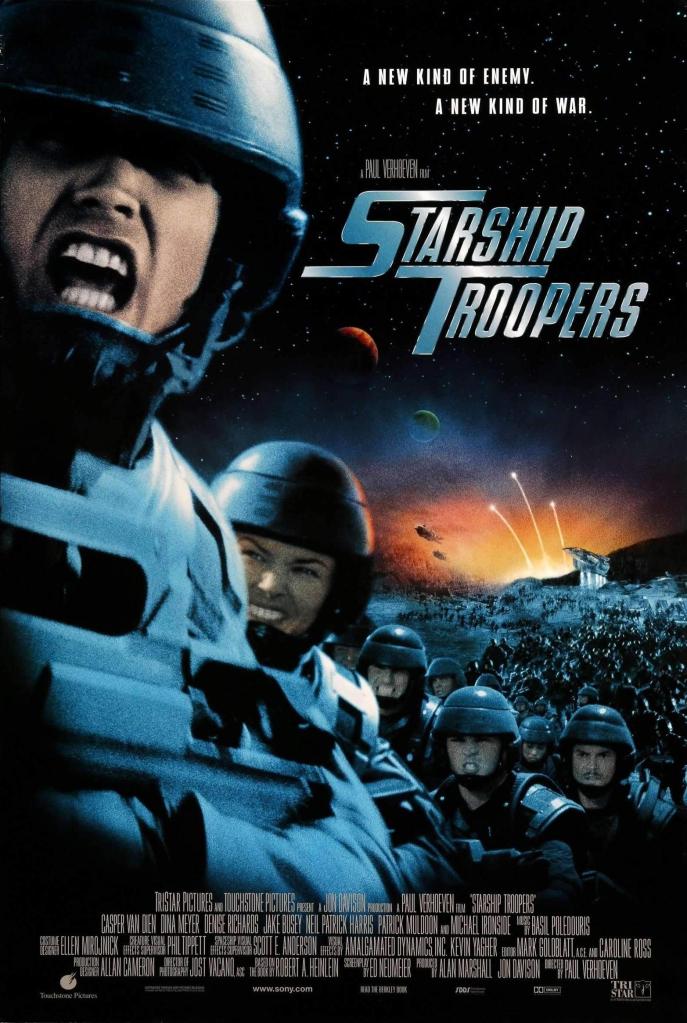

Changes from one medium to another are a necessity, because no two types of storytelling have exactly the same requirements or demands. I don’t mind changes, provided that making the change does not alter or pervert the spirit or intent of the original work, and here’s where I’m going to piss some people off, because Starship Troopers. It’s one of those movies that flopped when it came out but has grown a devoted following in recent years. That seems to happen a lot – something people disliked when it came out is rediscovered years later and lauded or, conversely, something that was once popular is hit with backlash and people suddenly declare that they never thought it was that good in the first place and they only saw it in the theaters 27 times “ironically.” I don’t do that a lot, honestly. I’ve certainly reevaluated movies after the fact, sometimes enjoying them more, sometimes less, but I don’t think I’ve ever done a complete 180 on a film. Which brings us back to Starship Troopers.

My friends, I’m here to tell ya that I thought it sucked then and I think it sucks now.

Fans of the movie praise Paul Verhoeven for making a witty sci-fi anti-war satire, a movie in which the entire human military is thinly painted as Nazis in training. However, none of this is applicable to the book, which is most certainly not anti-war, nor is it in the practice of making the humans into the bad guys. In fact, the book – which I should admit I was already a fan of before the movie was made – isn’t really plot-driven at all, but is more of an examination of the life of a soldier in a hypothetical science fiction future. The war against the insectoid aliens is there, but it’s more of a backdrop, a way of examining the world that author Robert Heinlein created. It’s no surprise, then, to find out that Verhoeven admittedly never even finished reading the book, finding it too “boring” and “militaristic.”

Sir, I must say this: if you can’t even finish reading the source material of an adaptation, I submit that you are not the right person to adapt it.

Here’s the thing, folks: I have no objection to Verhoeven making an anti-war movie, or a satire, or a movie in which humans are thinly-disguised bad guys. This is his right as a filmmaker, and there are plenty of good movies that do just this. I do, however, have a strong objection to him doing so by trading in on a novel by Robert Heinlein which is none of those things. I simply don’t think it’s fair, either to readers of the novel or to Heinlein himself, and in disputes of this nature I’m pretty much always going to side with the original author’s intent. If Verhoven had made a virtually identical movie, changing the names and calling it something like Spaceship Soldiers instead, we would not be having this conversation right now…but it’s also possible that we wouldn’t be talking about the movie AT ALL, that without the connection to Heinlein, the film would have been forgotten entirely.

It’s not a question of which of these men I agree with more, it’s a question of whether it is ethically right of Verhoven to use Heinlein’s story to espouse views that Heinlein’s story clearly disagreed with. Personally, I don’t think it is. I know that this is an area in which a lot of people will disagree with me. Hell, maybe Heinlein himself would disagree with me. But I ask you this: Arlo Guthrie’s 18-minute song “Alice’s Restaurant,” which was essentially a protest against the Vietnam war, was made into a similarly anti-war film. Had Guthrie not been involved in the film, but rather it was made by somebody else who painted Guthrie’s character as a fool and his protest against the war as misguided, would that have been fair to Guthrie?

What I’m getting at, friends, is this: if you’re a fan of Starship Troopers, is your acceptance of the adaptation process based on which political viewpoint you agree with? If that’s the case, I’m afraid that we will not be able to meet halfway on this one, and I hope that we can still be friends and that you’ll still come back next week when I’m writing about how awesome the theme from DuckTales is or something.

Adapting a story from one medium to another should be done for one of two reasons. First, if it is an exceptionally good story and you want to retell it for a different audience. Great! Do it! But if it IS an exceptionally good story, then why do you want to change it?

The second, more cynical reason, is because the story is popular, and you’re hoping to make money by appealing to the pre-existing audience. Okay, I can live with that. But if the story IS already popular and has a pre-existing audience, WHY DO YOU WANT TO CHANGE IT?

The answer, by the way, is because writers can be a vain bunch (yes, I am including myself in that number) and a good number cannot resist the urge to put their own stamp on something. This is what Richard Kelly did (remember him?) in his Holes adaptation. He wasn’t writing an adaptation of Louis Sachar’s novel Holes, he was writing a Richard Kelly movie that was vaguely suggested by a novel by Louis Sachar. And for a fan of Louis Sachar’s novel, that would have been MASSIVELY disappointing.

But writers do this anyway, because for some people it’s more important that something is “theirs” than it is that they treat the source material faithfully. Sometimes that means they’ve created a brand-new breakout character, like the people who gave us Scrappy Doo. Sometimes that means “updating” a story for a whole new audience, the way the smash hit film Barb Wire “updated” the story of Casablanca to become beloved by the ages. And sometimes it’s because the author is just trying to trade on somebody else’s work to spread their own message to the masses, which makes me wonder how strong a storyteller you actually are if you can’t get your message out without borrowing somebody else’s name.

I’m not saying it’s impossible to do a complete re-imagining of a work and do it well. The Netflix miniseries Fall of the House of Usher is an excellent example. Writer/director Mike Flanagan didn’t even TRY to do a straight adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story. Instead, what he did was grab bits and pieces of dozens of DIFFERENT Poe stories and reassemble them into something totally original and unique. It was as if he had gotten his hands on ten different Edgar Allan Poe Lego kits, threw away the instructions, and used the bricks to create his own thing. It was fantastic, and is one of the projects I point to when I say that Flanagan is, in fact, the right man to adapt Stephen King’s The Dark Tower if anyone ever has the guts to give him the money to do it. But he didn’t do it by twisting or changing Poe’s work into something unrecognizable. Quite the opposite – he did something that was totally his and slipped in recognizable elements to help us see the larger picture.

Then there’s the wild movie that actually gets its name from the process we’re talking about, Adaptation, which is ostensibly an adaptation of Susan Orlean’s nonfiction book The Orchid Thief. The book is a portrait of a horticulturalist who was arrested for poaching flowers, but that’s not the movie screenwriter Charlie Kaufman wrote. Instead, he wrote a movie about how he (Kaufman himself, as a character in the movie) struggled with adapting the book. He fictionalizes Orlean and John Leroche, the subject of the book, and creates a fictional twin brother for himself – both Charlie and “Donald” Kaufman are played by Nicolas Cage in one of those movies that earns him his reputation of doing kind of insane movies. Orlean herself was understandably taken aback when she read the script, but in more recent interviews has said she’s come around and now loves the movie, which was in no way a literal adaptation of her work but still successfully communicated the book’s themes of longing and obsession. Also there’s a car chase.

Most adaptations, I think, usually fall somewhere in-between the highly faithful Holes and the bonkers left turns of Adaptation. I always point to The Wizard of Oz here – most people’s version of Oz is the one we saw in 1939, the Judy Garland movie that has become a legitimate cultural classic. It’s a lovely movie, it’s beautifully filmed, and the music is timeless. As an adaptation, though, it’s mid. The film leaves out lots of sequences from the book, compresses two good witches into one (making Glinda seem like kind of a jerk for not telling Dorothy that the Ruby Slippers could send her home at the beginning, whereas in the original book those are two entirely different witches and the first apparently doesn’t know), and changes a few things – most egregiously the ending, which implies that Dorothy’s journey to Oz was just a dream. This is not at all suggested by the book, but the ending of the film has become so iconic that it’s inspired a thousand other “all just a dream” endings, which – speaking as a writer – is a crime I consider only slightly worse than lighting an orphanage full of puppies on fire and chaining the doors on your way out. But even then, the sense of wonder and awe that the film gives us DOES successfully communicate the wonder and awe of the book, and for that reason I can still love it.

A good adaptation has the potential to breathe new life into an existing work. A bad one, though, has the power to choke a work to death. If it ever comes down to a choice between one or the other, I know which side I’m going to be on.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His most recent writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, volume one of which is now available on Amazon. You can subscribe to his newsletter by clicking right here. He’s not kidding about the theme from DuckTales, you know. As TV themes go, he dares you to name more of a banger.