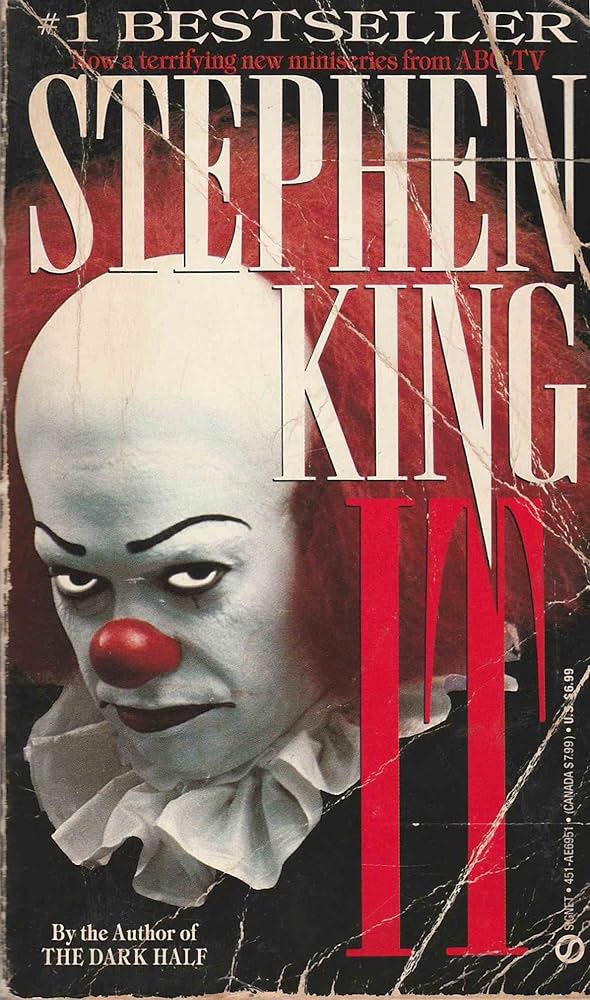

“Hey,” one of my students whispers to the kid sitting next to him. “He’s reading It.”

And I smile.

On the wall in my classroom is a small whiteboard. At the top of the board is written “What is Mr. Petit reading?” Underneath, I regularly update the board with the title and author of whatever book has most recently been removed from my To-Be-Read pile and is actually in the process of being read. Currently, that book is Stephen King’s It. I’ve had that board up for a few years now, and I update it whenever I begin a new book, and having it visible has led to lots of really great questions such as “Are you still reading that one?” and “How many books do you read, anyway?”

Occasionally, though, the board can lead to an actual conversation if a student happens to have read the book, is curious about it, or didn’t know that a book even existed (for properties they’re only familiar with as movies, such as Ready Player One). It is the book currently on the board, and it’ll probably stay there for a little while, because even for Stephen King, it’s kinda long. Some students are horrified when I tell them that I’m reading a book that’s in the ballpark of 1100 pages. They are even more baffled when I tell them that this is not the first time I’ve read it. I don’t recall, honestly, if this is the third or fourth time I’ve taken this particular trip to Derry, Maine, but I know exactly when the LAST time I read it was – it was late August and early September of 2017, and I remember it because it happened to be the book I was reading the week my son was born. I recall sitting there, scrolling through the pages on my tablet as Erin and Eddie slept, each of them rather exhausted after recently undergoing the most dramatic moving day in the history of a human being.

Don’t worry, I didn’t whip out my book and start reading as soon as the kid popped out – this was some time later, as we had to stay in the hospital a little while as they treated him for some blessedly minor things that prevented us from going home for about five days. If you’ve ever spent time in the hospital, no matter how serious the condition may be, you’ll know that after a few days you start crawling up the walls if you don’t have something to do. My something was to visit with my friends in the Losers Club.

The specific reason I started reading It again this week, though, is because I finished the first season of HBO’s TV series Welcome to Derry, a prequel to the film adaptations of the novel from 2017 and 2019. The series is produced by Andy Muschietti, who directed the films and half the episodes of the show as well. I thoroughly enjoyed the series, and it made me thirst to go back and revisit the source material again. As I’m reading it, I’m noticing the little bits and pieces, the tidbits the writers and showrunners planted in the show that help build out the world with water from the original font.

To be clear, this TV series is a prequel to the MOVIES, not the book. There are some important differences that prevent it from working as an adaptation of the novel, chiefly the time period. The original novel is set in two eras: 1958 (when the protagonists are children) and 1985 (when they return to Derry as adults to finish what they started). The creature they do battle with has a cycle of about 27 years in hibernation, after which it returns to wreak havoc on Derry once again. 1985 was contemporary when the book was written, but Muschietti decided to keep the story set in the “present” when the films were released, meaning the events were shifted to 1989 (for the kid portions) and 2016 (for the adult portions). Welcome to Derry details the previous cycle of It in 1962. The point is that the movie universe cannot fit the timeline of the book universe, and that’s honestly not a bad thing.

Since the show, from the outset, cannot be a direct prequel to the novel, Muschietti and the writers are playing a little more fast and loose with the story, while still paying respect to it. For example, in the original novel Veronica Grogan is the name of one of the countless victims of Pennywise during the monster’s 1958 cycle. The TV show elevates her to one of the main characters fighting against the clown in the generation BEFORE the Losers’ first encounter with the monster. The names of many other characters from the book are peppered throughout the show, some of them characters mentioned in the novel, others with names that imply (and in a few cases, make abundantly clear) that they are relatives or ancestors of characters from the original in this version of the story.

But the connections to the works of Stephen King don’t end with elements strictly from It. At one point, a character is sent to Shawshank Prison, the setting of King’s classic novella (and its classic movie adaptation) The Shawshank Redemption. Shawshank is frequently referenced in King’s Maine-centric stories, which is to say a little more than half of them, so it’s not a surprise when it turns up here. An even bigger link, though, is the character Dick Halloran. Halloran is one of the principal characters in his novel The Shining, which was written before It, and the original novel reveals that he was somehow involved in the tragically violent events that concluded a previous cycle of It. Welcome to Derry expands upon that, showing those events in full and giving Halloran a much more significant role. What’s more, they don’t even stop there, referencing elements of Halloran’s character that come neither from It OR The Shining, but rather from the latter’s sequel, Doctor Sleep.

What I’m getting at here is that Welcome to Derry feels like it’s inching closer and closer to something that Stephen King fans have wanted to see for a very long time: a true cinematic universe.

Yeah, we’re going to that well again. Marvel has its cinematic universe. DC is on take two. We’ve got one for Star Wars and John Wick and even horror franchises like The Conjuring. But the thing you need to remember is that none of these franchises INVENTED the idea of a shared universe. It’s been around for a very long time. William Faulkner linked several of his novels and short stories together via the inhabitants of the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi. James Joyce’s Dublin serves as the backdrop for several of his stories and, inasmuch as it’s possible to understand anything Joyce wrote, several of them link together. And King, much like many other contemporary writers, delights in dropping in Easter Eggs, hints, clues, and references that tie his various stories to one another.

Now not ALL of his stories can be said to definitively take place in the same universe. The Stand, for example, is a novel about a virus that kills most of the population of the world, which clearly precludes most of his later works from being set in the same universe. Cell isn’t exactly a zombie story, but it’s close enough that this world is incompatible with most of King’s other work. And it’s hard to reconcile the bleak, horrific vision of the afterlife from Revival with several of his other stories which feature good, even friendly ghosts on occasion, such as Bag of Bones. Then there are the Stephen King books that explicitly reference other King books – or their movie adaptations – as fiction. That’s a bit of a roadblock.

On the other hand, King himself has provided us with a handy device that can explain away any discrepancy via his Dark Tower series: a multiverse. The Tower itself is a sort of central hub around which all reality converges, and that includes many different worlds and dimensions that are similar to, but distinct from, one another. The Dark Tower provides links not only to It and The Stand, but to multiple other books and short stories. And lots of the other stories he’s written drop in casual references that remind us that yes, their universe is one of the countless that are connected to the Tower.

So all that said, why HAVEN’T we gotten a proper Stephen King cinematic universe before? The biggest obstacle, frankly, is licensing. King’s first novel, Carrie, was published in 1974, and he’s been turning out book after book and story after story since then. The most recent count I can find credits him with 67 novels and novellas and over 200 short stories over his 52-year career, and he’s been selling off the rights to them to different players all along. I don’t begrudge the man this – Lord knows I wish I could get that kind of payday – but the result is that the film and television rights to his works are all over the place. Dozens of studios and even individual filmmakers own bits and pieces of him, and getting all of them together to play nice and collaborate seems like a pretty impossible prospect. It’s the same reason that Marvel characters didn’t start meeting each other on screen until Marvel Comics stopped selling the rights to anybody who offered them twelve dollars and half a Fruit Roll-Up and started making the movies themselves.

It’s not like King isn’t still a significant player in the entertainment game. People who don’t follow him may think of his work primarily as the grist for a huge slate of horror movies from the 1980s, but they’ve been coming out regularly since then – and they’re not all horror. 2025 brought us no less than four big-screen adaptations of his work: The Monkey (which turned a straight horror short story into kind of a bizarre black comedy), The Life of Chuck (a beautiful and faithful adaptation of a semi-fantasy by director Mike Flanagan), and two adaptations of books he wrote under his Richard Bachman alias, The Long Walk and The Running Man. These last two are both dystopian science fiction rather than horror, but they’re radically different from one another, despite the fact that they both have the same hook of characters competing in a lethal game in the hopes of a life-changing prize. But while The Long Walk is a dark, nihilistic societal commentary, The Running Man is a slam-bang action film.

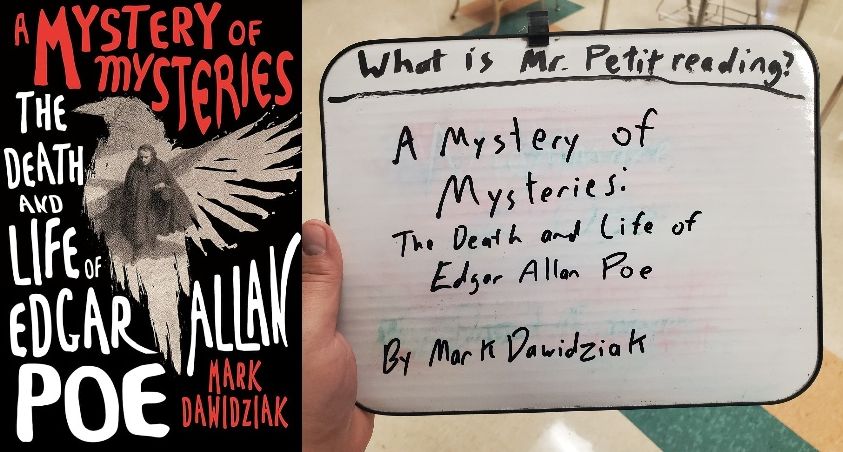

There have been attempts in the past to create a sort of King universe. Most notably, in 2018 Hulu produced Castle Rock, a series “inspired” by elements from a great number of King’s various works and set in that OTHER town in Maine that seems like it must be a nightmare to actually live in. The show was okay and it lasted two seasons, but I don’t think it actually gave fans what they wanted: a world in which the stories they love (or at least versions of those stories) could coexist. In Castle Rock, it was more like they took chunks of King’s books – characters, names, places – and pieced them together into something different. That’s a legitimate storytelling technique, of course. Mike Flanagan did it with Edgar Allan Poe for his exquisite miniseries version of Fall of the House of Usher. But it wasn’t quite what we were looking for.

In Welcome to Derry, the events of the two It movies are canonical, and the things we’ve seen so far make it quite easy to link that world with The Shawshank Redemption and the Shining/Doctor Sleep duet – if not exactly the movies we’re familiar with, then at least some version of those events. All of those movies, it should be pointed out, were released by Warner Bros., which is no doubt why they could play with those toys so easily. The show has not officially been renewed for a second season, but it has achieved real critical acclaim (although, typical for a streaming service, we have no idea what its numbers are), and Muschietti has been quite vocal about his plans for the next two seasons of the show. Future seasons would tell stories of two earlier iterations of the It cycle, in 1935 and 1908. This, I think, would be the perfect opportunity to build out the universe and add more parts of the Stephen King world. In fact, I think in some ways it would be almost REQUIRED to do that.

I loved season one of Welcome to Derry. The story was tense and compelling, the performances were great, and even though King wasn’t directly involved, the new characters all felt like the sort of characters that we get attached to in his books – ordinary people who get swept up in something far beyond their comprehension. If there is one legitimate complaint about the show, though, it’s probably that about half of the plot (the half that focuses on the child protagonists rather than the adults) is a bit TOO similar to the original It: a bunch of outcast children band together to stand against the evil of Pennywise the Clown. If we’re going to do another two seasons, they can’t just be two still-earlier stories about kids teaming up and fighting the monster. They need to bring something else to the table.

Andy Muschietti, I think, has proven himself an able enough storyteller that he is no doubt aware of this fact. The way he’s talking, it seems like he already knows what the story will be in 1935 and 1908. What I’m hoping is that he finds ways to tie in to other King stories. Could there potentially be references to John Coffey or the other characters from The Green Mile (set in 1932 in the novel, but it wouldn’t be outlandish of them to drag it forward in the timeline a few years)? Could we see the immortal vampires of ‘Salem’s Lot or the origins of the mysterious government project called “The Shop” from books like Firestarter? All of these, of course, would depend on rights issues in various ways, but I don’t think any of them are impossible either.

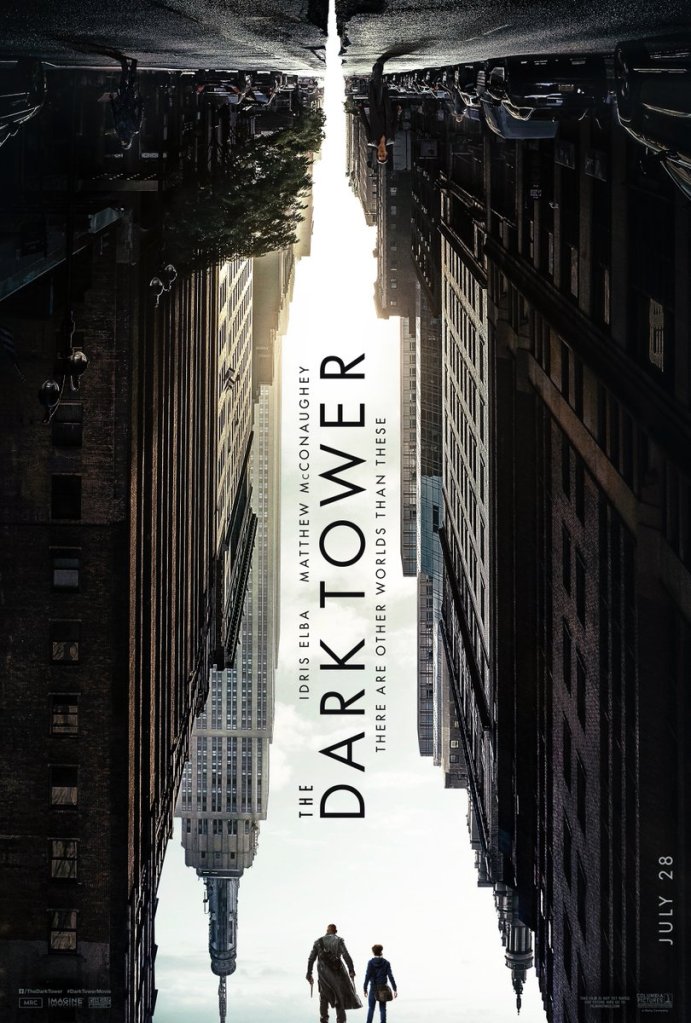

Then there’s The Dark Tower itself, the rights to which currently reside with the previously mentioned Mike Flanagan. There was an earlier attempt to put the story of Roland of Gilead to film, a 2017 movie that foolishly tried to condense seven novels (all but one of which fall into doorstopper territory) into a 90-minute feature, and fans were not pleased. Flanagan, who already has several well-received King adaptations under his belt, has expressed the desire to use The Dark Tower for a television series of about five seasons, with a pair of movies to conclude the story. This is a much smarter approach to the material, and Flanagan has proven himself time and again to be someone perfectly suited to bringing Stephen King’s stories to life.

The optimal version of this, for me at least, would be for Flanagan’s Dark Tower to share fabric with Muschietti’s series. Characters common to both projects could be played by the same actors, the stories could be woven in concert with one another – separate, but linked. Could it happen? Well, Warner Bros. owns the rights to It and Welcome to Derry, so for this to happen, Flanagan would have to produce his series in cooperation with Warner Bros. It’s not out of the question. His previous development deal with Netflix is over, and his current deal with Amazon does not include The Dark Tower. He could take the story anywhere he wants. And he’s got a relationship with Warner Bros. as well – he directed their adaptation of Doctor Sleep and wrote the upcoming Clayface movie from DC Studios, which coincidentally, is ALSO in the Andy Muschietti business, as he’s been signed to direct their upcoming Batman movie, Brave and the Bold.

I’m not saying that this will happen. I’m not saying that Flanagan and Muschietti and Stephen King and Warner Bros. will join forces and finally begin to create the Kingamatic Universe that Constant Readers have been craving for the better part of five decades.

I’m not saying it’s going to happen.

I’m just saying it would be pretty damn cool.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His most recent writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, volume one of which is now available on Amazon. You can subscribe to his newsletter by clicking right here. He’s also started putting his LitReel videos on TikTok. He also hopes that somewhere in there they find a way to tell us what happened to the Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon…specifically, does she still love Tom Gordon, or has she moved on to – say – Shohei Ohtani?