When you’re a high school teacher and spend most of your day around teenagers, you will overhear their conversations whether you like it or not. You hear about the TikToking, and you know who is dating who, and on frequent occasions you learn more about the way these kids spend their weekends than you ever want to know and you contemplate duct-taping your own children to a pool table from the time they’re 13 until they turn 27 or so. And on rare, extremely rare occasions, you’ll hear them discuss things that are actually relevant to your class. Earlier this week, for instance, I overheard a few girls talking about why so many people are using The Great Gatsby as themes for parties and dances these days.

As always happens when there’s a conversation worth joining, I jumped in. “There are three reasons,” I said. “First of all, it’s the 20s again, so people are playing with that. Second, the book went into public domain a few years ago, so nobody has to pay to use these things. And third, there are a lot of people who think the movie is fun and didn’t actually pay attention when they were supposed to be reading the book.”

The Great Gatsby is, of course, a seminal work of American literature. It’s one of the best books ever written in this country, and it paints a complex and gripping narrative in a relatively short number of pages, but the book is about the unsatisfying nature of a decadent lifestyle and how pursuit of material things is shallow and destructive. Anybody who comes away from that book thinking that these characters are something to aspire towards is – and I’m going to be kind here – an utter moron.

I talked about this conversation with some of my English teacher friends (of course I have English teacher friends – we sit around and conjugate each other’s verbs and talk about which infinitives we’re crushing on) and discussed the fact that there aren’t a lot of books that we teach that provide role models or, for that matter, happy endings. Let’s face it, most books that are complicated enough for a really deep literary analysis tend towards tragic – or at best, bittersweet – endings. The least-depressing book I’ve ever used in my classroom is The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and that book BEGINS with the complete destruction of the planet Earth. And one of my friends in this chat commented that this is why she sticks to reading lighthearted stuff on her own time – “literature” is too depressing.

I’ve always thought it was odd to use the word “literature” as a genre, the way I would “science fiction” or “horror.” What, exactly, qualifies something as a work of literature? Every time I walk into a bookstore with a “literature” section, I want to ask somebody who decides which books go on those shelves and which ones do not? Isn’t the very existence of a “literature” section sort of a low-key insult to all of the other books in the store that got shelved somewhere else? Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea goes on the literature shelves whereas William Goldman’s The Princess Bride doesn’t, but I could write you a whole dissertation on which one is a better book, and it ain’t the Hemingway.

Is it just the age of the work? Everyone would agree that Lord of the Flies from 1954 is a great work of literature. But what about Robert Heinlein’s Rocket Ship Galileo, published in 1947? It’s not only a book that doesn’t enter the “great literature” discussion, it’s not even usually part of the conversation when you talk specifically about the work of Robert Heinlein. We got George Orwell’s 1984 in 1948, nearly twenty years after the first Nancy Drew novel, The Secret of the Old Clock, but nobody is citing the works of Carolyn Keene in the conversation of great writers. And that’s not just because she didn’t actually exist.

Is it just about the complexity of the work? Must a work deal with heavy ideas and deep themes to qualify? The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn gets my personal vote for the greatest American novel ever written (sorry, F. Scott Fitzgerald). Set 20 years before the Civil War but written about 20 years afterwards, the novel is a deep and fascinating analogy about the changes the country went through during that time period. Whereas Mark Twain’s earlier book with these characters (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) was a simple boy’s adventure story, Huckleberry Finn is about a child struggling with the ethical quandary of whether it is morally right to help his friend Jim escape from slavery. Jim’s owner, Miss Watson, has taken care of Huck, and in the eyes of the law he is betraying her by helping in Jim’s escape. But eventually, he comes to the conclusion that he’s going to be loyal to his friend, even if it goes against the law, even if it goes against what he has been taught is morally right. The book deals with the destructive nature of bigotry, ignorance, and hypocrisy, and Huck himself becomes symbolic of the moral transmogrification that the United States was beginning to undergo. In other words, literature.

The thing is, though, a lot of these same ideas and themes can also be found in random episodes of Star Trek. If I pull out Oliver Crawford’s script for “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” I can get into a deep conversation about the folly of racism as we watch two aliens whose species has hunted itself to extinction because some of them are black and white whereas others are white and black. It’s a legendary episode, but could I justifiably call the script for it literature the same way I would Huck Finn or – to use the other best-known example of anti-racist literature – To Kill a Mockingbird? Most people would say no.

I posed this question, this “what is literature” question, to my English pals, and one of them said she once looked it up herself and read one of the characteristics that makes something literature is a focus on character and their development rather than plot. Does that really work, though? Gatsby is a very deep examination of the characters, but none of them actually CHANGE. By the end of the book, they (the ones that survive, anyway) are all the same shallow, soulless people they were when the story began and only the narrator – the criminally bland Nick Carroway – has shown any development at all, that development being disgust at the people around him. It’s like you’re left feeling when you watch the final episode of Seinfeld.

On the other hand, my friend pointed out, the male lead in Fifty Shades of Grey seems to change by the end of that series, becoming actually devoted to the narrator. I’ll let you draw your own conclusion as to whether this qualifies as development or not, I haven’t read Fifty Shades. But if there’s one thing everyone in our English chat can agree on, it’s that Fifty Shades of Grey does NOT qualify as literature.

I want to be clear here: I haven’t seen the movies, nor read most of the books. I’ve read exactly one page, the first one, in a bookstore. I was curious as to what the big deal was, and after reading one page I said – out loud – “Oh good LORD,” and put it down. It’s not that the book is smut. If you want to read smut, go right ahead, I don’t judge you for it at all. I will, however, judge you for reading such POORLY WRITTEN smut when there is smut of much better quality readily available. I’m not telling you not to read Fifty Shades because it’s explicit, I’m telling you not to read it because you deserve better smut.

Or believable characters, genuine titillation, or a functional understanding of the culture it purports to depict.

Is it the fact that something is “highbrow” what makes it literature? Well that comes with the same problem as designating something literature in the first place: who decides? To pull the Shakespeare card again, my students are ALWAYS intimidated when we start reading Hamlet because they think of Shakespeare as something for “thinky” people. Sure, that may be the way he’s considered today, but in his own time, Shakespeare was a popular writer. He was turning out play after play for the masses, and because he knew exactly what the people wanted, he loaded them with sex and violence. He was the J.J. Abrams of the 16th century. The kids don’t get that, though. If you understand what he’s actually saying, Hamlet’s line “Do you think I meant country matters?” is just as raunchy (and way more clever) than anything E.L. James wrote, but in all my years of teaching the play I’ve never had a student pick up on the subtext. Only a few of them get the later, more obvious line when Claudius is seeking Polonius’s corpse and Hamlet tells him Polonius is, “in heaven…if your messenger find him not there, seek him i’th’other place yourself.” Every so often I have a kid who asks, “Did he just tell the king to go to Hell?” and that student automatically becomes my favorite.

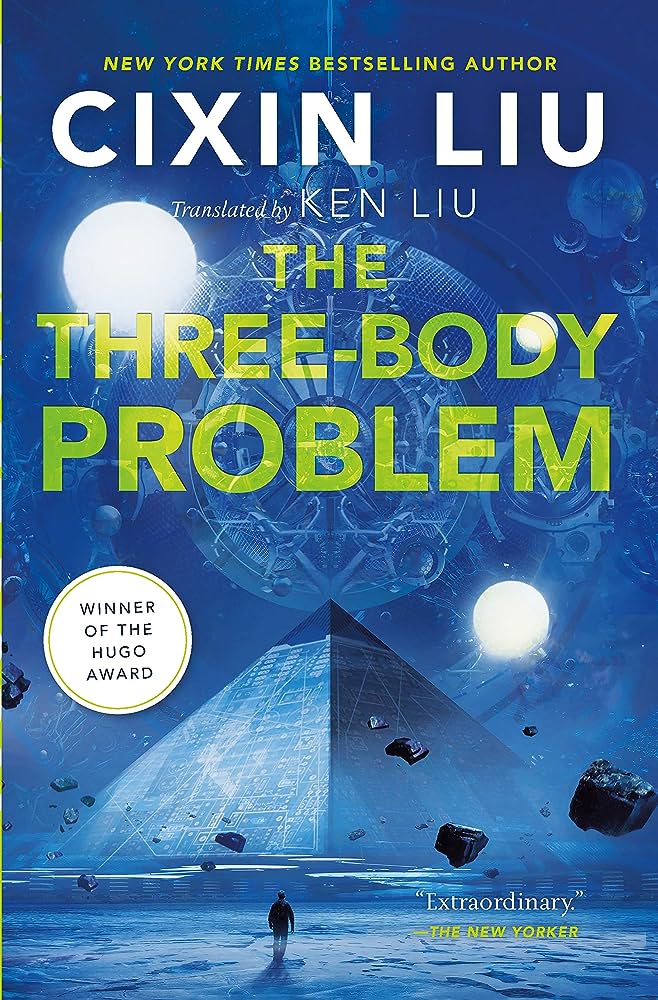

The bar can’t be whether something makes you think. Last week I finished reading Liu Cixin’s novel The Three Body Problem, and that’s one of the thinkiest dang books I’ve ever read. The book follows a large cast of characters who discover a secret organization attempting to prepare Earth to be conquered by extraterrestrial invaders. This is, I must stress, an extremely barebones description of the plot, and deliberately so. This story is far deeper and more complicated than my pitiable attempt to summarize it. In fact, if someone tried to argue that it’s the best science fiction novel of the 21st century so far, I will have absolutely no ammunition with which to disagree with them. This Chinese novel was originally serialized in 2006, published as a novel in 2008, and first published in English in 2014, so no matter which edition you’ve read, it’s less than 18 years old. As such, it’s not something that I hear come into the conversation when people discuss “literature.” Not YET, anyway. Come back in 20 or 30 years and that may well change. But is it only the relative youth of the book that keeps it off the table?

Maybe it’s a combination of all of these things. Maybe “literature” has to be deep AND intelligent AND kind of old. Maybe all these things that we now call “literature” are only in that category because they’re the best examples of their time period and we’ve forgotten 90 percent of the utter crap that was written around the same time. That’s not only possible, I think the further back in the history of storytelling you go it becomes almost undeniable. The poet W.H. Auden once said,“Some books are undeservedly forgotten; none are undeservedly remembered,” and by this I think he was trying to tell us that people will hopefully still be reading The Three Body Problem in the year 2100, whereas by then hopefully the only people who remember 50 Shades of Gray will be literary historians who cannot figure out why readers were so temporarily obsessed with a piece of mediocre Twilight fan fiction.

Increasingly, when it comes to the question of literature, I find myself using the late Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s description of “obscenity.” Unable to actually define the term, he simply said, “I know it when I see it.” That’s how I feel about literature, too. But my opinion, of course, doesn’t count for more or less than anybody else’s.

Except for that guy shelving the “literature” section at Barnes and Noble. He apparently holds a little more sway than the rest of us.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His most recent writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, now complete on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform. He doesn’t know if anyone would ever call the new trilogy version of that series, beginning with Little Stars Book One: Twinkle Twinkle, “literature,” but he DOES know it will be available in both paperback and ebook beginning on May 4, and he is CRAZY excited about it.