The digital revolution has made it easier than ever for people to make movies and TV shows. You can do virtually every job that’s absolutely necessary to make a film with nothing more than a smartphone and the right apps, and people have begun to do so. This does nothing to increase the talent of the people involved, of course. Even that doesn’t seem to be a hard obstacle, though, if the YouTuber my son watches called “Granny” is any indication. (She’s a nutcase who puts on a wig and a muumuu and rides an adult tricycle to fast food joints and orders food in a horrifically cloying voice. Although I do not advocate this behavior, I guarantee you she’s gotten a lot of saliva in her food.) What’s more, there are thousands of avenues to share the content – dozens of streaming services, almost as many social media platforms. For an entire generation, consuming media in bite-sized tidbits on your phone is not only the norm, it’s the preferred method of being entertained.

God, do I hate that.

I know I’m going to sound like a crotchety old man, but there’s a good reason for that: I am a crotchety old man. I don’t like watching stuff on my phone, not when I’ve got a perfectly good television. And I don’t like 30-second bursts of “content.” I’m a storyteller, and when I watch something I want to watch a story. And while telling a satisfying story in 30 seconds is certainly not impossible, it is tremendously difficult, and there are very few people on TikTok who have proven themselves up to the task. No, while my students may swarm around a clip of someone sending a pizza to the wrong house and giggle as though there’s something clever about that, I’d rather watch ten episodes of a science fiction epic telling a serialized story that gives time to develop character, theme, and an entertaining arc.

Even a television is not the optimal way of viewing a story, though, although that’s how I do most of my viewing. It’s fine, don’t get me wrong, especially in this day and age when your home system can have an amazing picture and stereophonic 4-D quantum sound, if you’re the kind of person who has the sort of money to burn on such a system. But that doesn’t do it for me – nothing does it for me – like sitting in a movie theater.

I know all the arguments against going to the movies, of course. Yes, it’s expensive (and just getting moreso, with AMC’s recently-announced scheme to charge more for better seats). Yes, the concessions are overpriced. There are frequently rude people in the theater as well: people who talk during the movie, people who come in late or trip over you while spilling their popcorn, people who (and this should be a criminal offense) turn on their phones, the glare blinding you at a critical moment of the narrative. And damn it, you can’t pause it to go to the bathroom. There are dozens of very solid arguments in favor of watching movies at home instead of in a movie theater.

My point is: I don’t care.

All of those complaints are true, valid, and they annoy me as much as anyone else, but the long and short of it is that when I’m excited to see a motion picture, there is no better environment in which to do it than in a darkened room with minimal distractions surrounded by other like-minded people who are there for the same thing. The first movie houses were just vacant vaudeville theaters with a screen put into place, but from the very beginning they found the perfect way to experience a film. When you watch a movie at home, it’s far too easy to get pulled out of the world of the story. The sun is coming in through the window, you’re getting Facebook notifications and text messages, your child keeps handing you his magna doodle and telling you to draw a picture of the Burger King logo. Those things don’t happen in a movie theater – or at least they shouldn’t, if you turned your phone to “do not disturb” like a civilized human being.

What’s more, no matter how great the home theater experience becomes, the “home” part will never be able to match the thrill of being in a theater with hundreds of other people who are there for the same thing as you. Think about the first time you saw Avengers: Endgame. When Thor’s hammer lay on the battlefield and was picked up by a mysterious figure, the room grew silent. Moments later, when it smashed Thanos in the face and returned to Captain America’s hand, the theater exploded. I have never experienced a simultaneous eruption of joy in a movie theater to rival that moment, and I don’t know that I ever will again.

Think about Attack of the Clones. It is, if I’m being honest, my least favorite Star Wars movie, but I will always treasure the memory of the midnight screening I attended and how the fans roared when Yoda took out his lightsaber for the first time. Even bad movies are made more fun with an audience. Nobody is going to argue that the Green Lantern movie was great cinema, but there was a load of fun to be had in my New Orleans-area screening because the movie was filmed in our area, and we all laughed together as we saw familiar streets and landmarks that they tried to pass off as being in California.

I’ve seen a lot of great movies in my life, and I’ve seen a lot of them at home. But every great movie experience I can remember happened in a theater. It’s like being in a more benign version of Plato’s cave, a magic candle shining excitement on the screen. You can’t do that at your house.

Movies serve as landmarks in my memory, too. I remember, as a child, going to the movies with my parents, my brother and sister, and each time considering it a treat. I know that I saw Ernest Goes to Camp, Santa Claus: The Movie, Batteries Not Included and Masters of the Universe that way. I remember seeing Forrest Gump with my dad in a sadly-defunct dollar theater the week before I graduated high school. I wish I knew what the first movie I ever saw in a theater was, but unfortunately my memory isn’t that good.

I got older and my friend Jason and I started going to the movies almost every weekend, sometimes two or three movies a week. Jason ran a video store back when those still existed, so it was market research for him, but we both just loved the experience of going, of watching, of holding out our thumbs to indicate approval or disapproval for the trailers that flickered across the screen. It was with Jason, watching the wrestling movie Ready to Rumble, that I started to think about superheroes being run like the WWE, a germ of an idea that eventually led to my first novel, Other People’s Heroes. Thanks, awful movie!

I know the first movie Jason and I saw at the local Palace Theater the weekend it opened (The Lost World: Jurassic Park.) I know the first movie I saw with my girlfriend Erin (Madagascar), the movie we saw the night before I asked her to marry me (Skyfall), the last movie we saw before our son was born (The Dark Tower) and the first movie we left Eddie with a babysitter to watch (It Chapter One – my history with Erin is inexorably tangled with the works of Stephen King, a story which will probably be its own column at some point).

All of this is to say that on Tuesday I added another memory to the cinematic roadmap of my life: the first movie we took our child to see in a theater.

I need to explain a few things to help you understand just how significant this is to my family. I don’t know that I ever really believed I would get to be a father. It just wasn’t something that I thought was in the cards for me, and I’ve never been happier to be wrong. Being Eddie’s dad is the greatest thing in my entire life. But it hasn’t been free of challenges. Some time after Eddie turned one year old and he still wasn’t talking, we started to get concerned, and we eventually managed to confirm that he’s on the autism spectrum. Any child comes with challenges, but his were different from many others. He started reading early and he’s terribly smart (this is not just a proud parent talking, we’ve been told this by numerous doctors and teachers), but he also tends to fixate on things like logos and clocks. His obsession with time in particular is perplexing to me. And of course, there was the talking, which for the longest time he simply was not interested in doing.

He talks now, he virtually never stops talking now, but there are a lot of milestones in his life that have come later than usual. It’s terribly difficult to get him to sit still, he has trouble with disruption to his routines, and sometimes he has trouble with extreme stimuli. When he was two years old, for instance, we took him to my niece’s Christmas pageant at school. As soon as the audience applauded at the end of the first number, he began to scream in terror. I had to take him out in the lobby and sit with him there until the show was over. (Jason was actually there too, keeping us company, as his wife was one of the teachers at that school.)

So we were nervous. I was worried that he wouldn’t be able to deal with crowds and the stimulation of a movie screen, which would have made me terribly sad. Like I said last week, I don’t want to force my fandoms on the boy, but from the moment I knew we were going to be parents I wanted to share the things I loved with him.The idea that it might not be possible was heartbreaking.

But he’s older now, and he’s dealing with things better than he used to. He’s no longer scared of fireworks, for example, and this school year we brought him to another Christmas pageant and a band concert with no problems. So this week, with Eddie and I both out of school for Mardi Gras and assuming it wouldn’t be too crowded, we decided to finally try our hand at taking him to a movie theater.

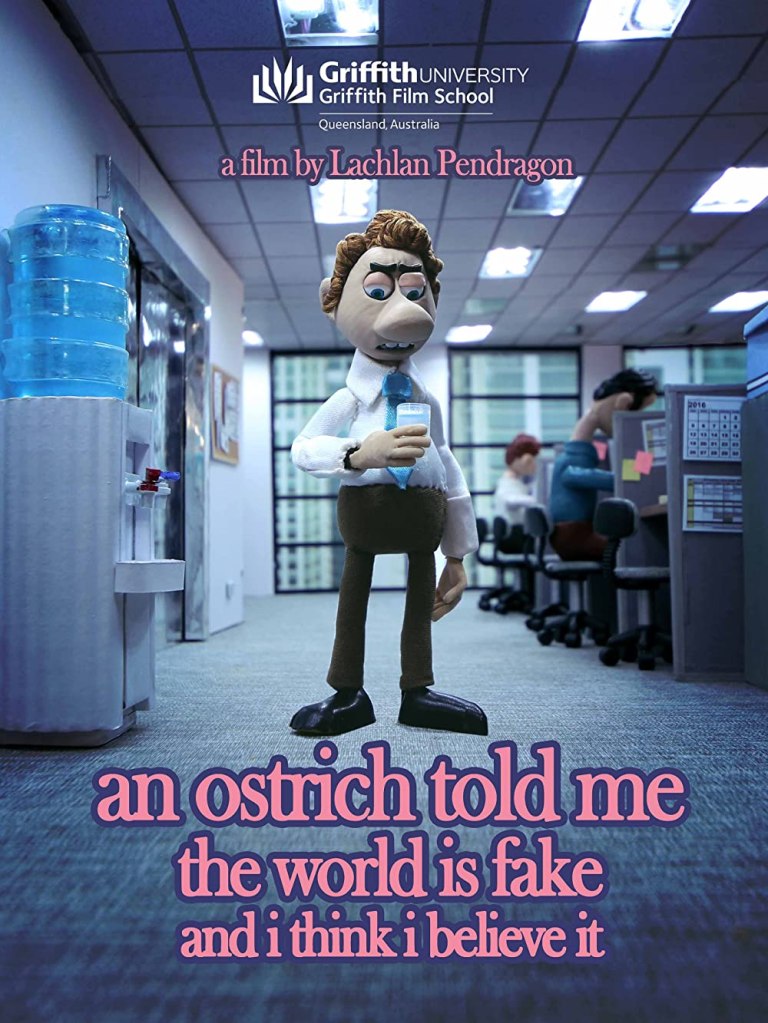

The only kid-appropriate movie playing was Puss in Boots: The Last Wish, so we got our tickets, which with my Stubs membership and the “discount Tuesday” promotion meant the three of us got to go to the matinee for less than $20. This, Erin said, made it easier to accept the fact that if Eddie wanted to leave, we’d have to just eat the ticket cost. What bothered me, though, was less the ticket price and more the fact that I have never walked out of a movie in my life. No matter how atrocious the film may be, I soldier on so that I can sound informed when I call it a piece of crap. It’s a matter of honor.

But for my son, I would take that risk.

Anyway, we got to the theater, we bought the boy some Sour Patch Kids and an apple juice, got a bucket of popcorn for the family, took our seats, and crossed our fingers.

I haven’t seen all of the movies in the “Shrek Cinematic Universe,” but The Last Wish is far and away the best of those I have seen. I never would have expected it from this movie, but the film turned out to be a serious meditation on aging and mortality with a positive and uplifting message about the importance of family and living life to the fullest. It was deep and meaningful, but without sacrificing moments of genuine comedy. The animation was gorgeous as well. Rather than giving us the plastic CGI that early Dreamworks movies sported, Erin pointed out that director Joe Crawford was borrowing visual cues from Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, with the same sort of staccato motion and faux-painted look to the imagery. It was lovely to look at and fun to watch.

More importantly than any of this, though, is that Eddie watched the whole thing.

He doesn’t always “watch” things at home. We’ll put on his cartoons and he’ll laugh and dance with the music, and his ability to pick up on a tune is wicked sharp, but he is easily distracted (even without text messages coming in) and wanders around the room, bouncing from one toy or activity to another, often oblivious to the entertainment on the screen. Here, with the lack of distractions, he kept his eyes on the film most of the time. He laughed at some of the funnier bits. He smiled a lot (I know this because I was watching him as much as the screen). And yes, he got a little antsy, looking at my watch frequently, although that is as much because of his obsession with clocks and time as it is anything else. He did ask “How much is left on the timer?” three times, but he never complained.

It’s warming my heart. Because again, I don’t want to force him to do things he doesn’t want to do, but if he enjoys going to the movies, I’m going to take him as often as I can. Sure, not as much as I went to the movies back in the day, I mean…I’m not going to take him to see Scream VI no matter HOW big a fan he is of Courtney Cox. But when there’s a movie for him, I want to bring him. He seemed into the trailer for The Super Mario Bros. Movie, coming in April. Pixar’s entry this summer, Elemental, looks cute. Heck, by the time Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse hits this fall, he may even be ready for that.

These were the things that went through my head as we watched the movie, of course. The real litmus test would be how he felt after the movie was over.

After we walked out of the theater, I asked him if he had fun. He said he did. I asked if he liked the movie with the cats. He said he did. He often agrees with random things, though, so I wasn’t sure if he was happy about it until later when asked to recap his day.

“What did you do today, Eddie?” we asked him.

His face beamed like it was washed with the light of that magic candle and he proudly proclaimed “I went to AMC Palace! I went to the movies!”

“That’s so great! What did you see at the movies?”

“Cats!”

Okay, so he’s still got some learning to do.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His current writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, a new episode of which is available every Wednesday on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform. He promises that this column won’t be about his kid EVERY week, but…hell, it’s gonna be about his kid whenever it feels appropriate. It’s his blog, after all.