Once again, it’s time for Five Favorites, that semi-regular feature here in Geek Punditry where I give you my five favorite examples of something. “Favorite,” of course, is a relative term, and is actually pretty fluid for me. I may think of something tomorrow that would supplant one of the choices on this list if I were to write this again. But for here, for today, I want to talk about five of my all-time favorite Santa Claus stories.

With Christmas only days away, the big guy is up north checking out his list, loading up the sleigh, and slopping the reindeer, so it only seems fair to me that I talk about some of the stories that have made him such a beloved icon to the young and the young at heart for centuries now. Let’s talk about the tales that make St. Nicholas so great.

The Autobiography of Santa Claus as told to Jeff Guinn.

This book, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, has long been a favorite of mine. You see, when Santa decided it was time to tell the truth about his life story, he recruited journalist Jeff Guinn to help him compose the book, a deep dive into the life of the man who was once known as Nicholas, Bishop of Myra.

If you’ve been reading my stuff for a while you’ve probably heard me talk about this book before, because it’s one I return to every few years. Guinn’s book mines actual history, including the true life of Nicholas, and combines it with a sort of subtle, beautiful magic. People expecting a superhero-style origin story for Santa Claus will be disappointed, because the truth is that Nicholas was just sort of “chosen” by unexplained forces, and to this day still doesn’t know why…but he knows that his mission is to give the world the gift of hope.

The story is lovely, and I love the way he mixes real history with fantasy. In fact, the history doesn’t stop with Nicholas’s life, but goes on to show Santa’s interaction with things like the composition of the song “Silent Night,” his influence on Charles Dickens and Clement Clarke Moore, and the lives of some of the very unusual and unexpected helpers he’s accrued in his many centuries on this Earth.

The book has two sequels. How Mrs. Claus Saves Christmas gives us a dive into Oliver Cromwell and his war on Christmas, and how Santa’s wife saved the holiday. The Great Santa Search rounds out the trilogy with a story set in the modern day, in which Santa finds himself competing on a TV reality show to prove who is, in fact, the true Santa Claus. All of the books are great, but the first one is my favorite.

Santa Claus: The Movie

If it’s a superhero origin that you’re looking for, though, this 1985 movie is for you. It was produced by Alexander and Ilya Salkind, riding the success of their Superman movies starring Christopher Reeve. And in fact, this movie is pretty much a straight rip of the structure of the first Superman movie: it begins with the character’s origin story (Santa and his wife are saved from freezing to death by the elves, who are there to recruit him), spends about half the film showing the hero’s development, and then introduces the villain at about the halfway point. From there we get to the real story, Santa fighting for relevance in a modern world where a corrupt toymaker is stealing his thunder.

I was eight years old when this movie came out, and that was apparently the perfect time to fall in love with it. I still love it. And David Huddleston – aka the Big Lebowski himself – is still my Santa Claus. When I close my eyes and picture St. Nicholas, it’s the David Huddleston version – his smile, his charm, his warm laugh are indelible parts of the Santa Claus archetype in my head. John Lithgow fills in Gene Hackman’s role as the villain, playing a cost-cutting toy executive named B.Z. who sees Christmas as nothing more than a profit margin. Dudley Moore is also along for the ride as Patch, one of the elves who finds himself in a bit of a crisis of faith.

It’s a shame that this movie never got any sequels, because it was set up in such a way that there were many more stories to tell, but it underperformed and apparently did major damage to Dudley Moore’s career. Before this he was a rising comedy icon, and afterwards he fell off the A-list. I still think it’s a fantastic movie, though, and I have to admit that when I watch it, I wonder what would have happened if John Lithgow had ever had a turn playing Lex Luthor.

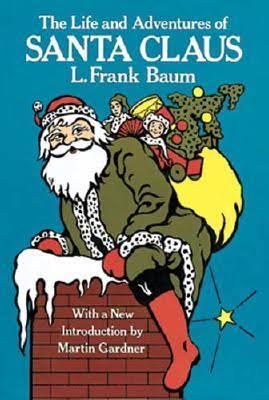

The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank Baum

For a different take on Santa’s origin, let’s wind the clock back to 1902. L. Frank Baum is riding the high of his hit children’s book The Wizard of Oz and he’s looking for a new project. Rather than return to Oz, though, he goes in a different direction and a different fairy tale – that of a young child abandoned in the woods and raised by fairies to become the most giving man in the world.

This is a very different take on Santa than most modern versions. It’s light on the fancy and heavy on the fantasy, with Santa being forced to do battle with monsters and creatures that are out to stop his quest to bring toys to children, and a conclusion that feels like it could have fallen out of the likes of Tolkien or C.S. Lewis. It’s hard to remember sometimes that the way we think about Santa Claus today was sort of codified by lots of little things over the early part of the 20th century – influences from poems, books, songs, and even the original AI-free Coca-Cola Santa Claus ads. But Baum’s book was before most of those things, and although his Santa doesn’t exactly jive with the Santa we know and love (no North Pole workshop, ten reindeer instead of eight, different fairy creatures instead of elves, and so forth), it’s still a fascinating read. It’s especially interesting if you’re a fan of the Oz books, as I am. This was two years before Baum would go back to his most famous creation and transform Oz from a single novel into a franchise, but it feels like it belongs in that “universe.” In fact, in later books Baum would link many of his unrelated books to the world of Oz through the connections of characters, other fairylands, and creatures that would grow in prominence. If you want to consider this the origin of Santa Claus in the universe of Oz, it’s not hard.

The Year Without a Santa Claus

Let’s get away from origin stories, though. We all love the Rankin/Bass classics, and their Christmas specials are legendary. In the top two specials, namely Rudolph and Frosty, Santa is just a supporting character. But they did give Santa a few specials of his own, and this second one is my favorite. In this 1974 Animagic classic, Mickey Rooney voices a Santa Claus that’s down with a nasty cold. This, coupled with a feeling of apathy from the children of the world about his annual visit, brings him to the conclusion that he’s going to skip a year. As the world faces the prospect of a Year Without a Santa Claus, it’s up to Mrs. Claus and a couple of helper elves to convince the big guy to pop a Zyrtec and get his act together.

This is the best of Rankin/Bass’s Santa-centric specials, although the most memorable thing about this cartoon isn’t Santa itself. We have this special to thank for the introduction of the Heatmiser and Coldmiser, battling brothers and sons of Mother Earth. They’re the best original Rankin/Bass characters by far, they have the best original song from any Rankin/Bass special by far, and even now you see them showing up in merch and decorations every year. It’s not easy for a new character to break into the pantheon of Christmas icons, but the Miser Brothers made the cut thanks to this awesome special and the fantastic musical arrangement of Maury Laws. The boys are a delight.

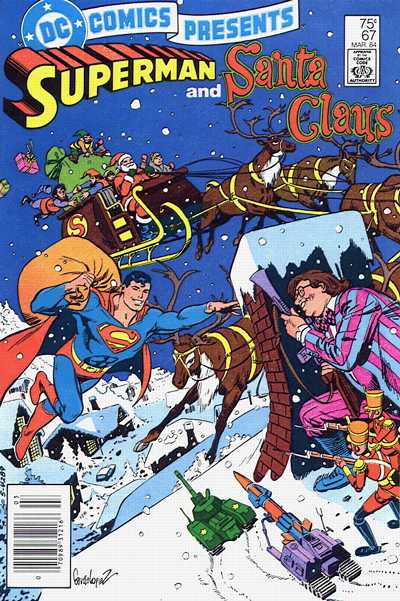

DC Comics Presents #67: Twas the Fright Before Christmas

Let’s wrap things up with this comic book from 1984. DC Comics Presents was a series in which Superman would team up with a different guest-star in each issue. Usually it was his fellow superheroes like the Flash, Batgirl, or the Metal Men. On occasion he’d have to partner up with a villain like the Joker. On more than one occasion he had to pair off with different versions of himself like Superboy, Clark Kent, or his counterpart from Earth-2. And on one memorable occasion he met up with He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, characters who were still on the rise.

But my favorite issue of the book is this one. Written by Len Wein with art by the most iconic Superman artist of the era, Curt Swan, in this issue Superman stumbles upon a little boy who tries to hold up a sidewalk Santa with a toy gun. Superman whisks the child off to his Fortress of Solitude at the North Pole where he determines that the child was hypnotized by a device in the toy, made by his old foe the Toyman. Leaving the Fortress, the boy’s toy zaps Superman with a burst of “white dwarf energy” which knocks him from the sky and leaves them stranded in the Arctic Circle. Luckily, they’re saved by some of the pole’s other residents. Superman and Santa then team up to save Christmas from the machinations of the sinister Toyman.

It’s a pretty silly story, but silly in a fun way. This is towards the end of the era in which Superman was allowed to be a little goofy, just two years before John Byrne would reimagine the character in his classic Man of Steel miniseries. And although that depiction of Superman has largely informed the character in the years since, it’s nice to see that modern writers aren’t afraid to bring back the kinds of things that made this story so memorable every once in a while. It ends with one of my LEAST favorite tropes, especially in a Christmas story (the whole “It was all just a dream…OR WAS IT?” nonsense), but that doesn’t diminish my love for it at all. I tend to go back and read this comic again every Christmas

Once again, guys, ask me tomorrow and there’s a good chance I would pick five totally different stories to populate this list, but as I write it here on December 20th, these are five of my favorite Santa Claus stories of all time. But I’m always open for new ones – what are yours?

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His most recent writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, volume one of which is now available on Amazon. You can subscribe to his newsletter by clicking right here. He’s also started putting his LitReel videos on TikTok. Honorable mention goes to a story John Byrne did for Marvel’s What The?! comic where Santa twists his ankle delivering to Latveria and Dr. Doom has to take over and finish his route for him.