A few weeks ago, San Diego Comic-Con happened once again and…well, once again, I wasn’t there. It’s kind of a little tradition of mine. Comic-Con happens and I stay at home. Like many storied, time-honored traditions, it kinda sucks. So I instead spent that weekend waiting for the news to trickle out online. There wasn’t anything major this year, nothing that knocked my socks off, no “Robert Downey Jr. is Doctor Doom” moments. There were, however, trailers. I love a good trailer, those little short films that give us a taste of an upcoming movie or TV show. They’re becoming a dying art, really, with so many trailers either failing to give you any excitement or – much worse – giving away half the thrill and excitement of the movie itself too early. If you haven’t seen the trailer for Project Hail Mary, for example, then I beg you in the name of all that is good and holy DON’T watch it. It gives away one of the best reveals in the book.

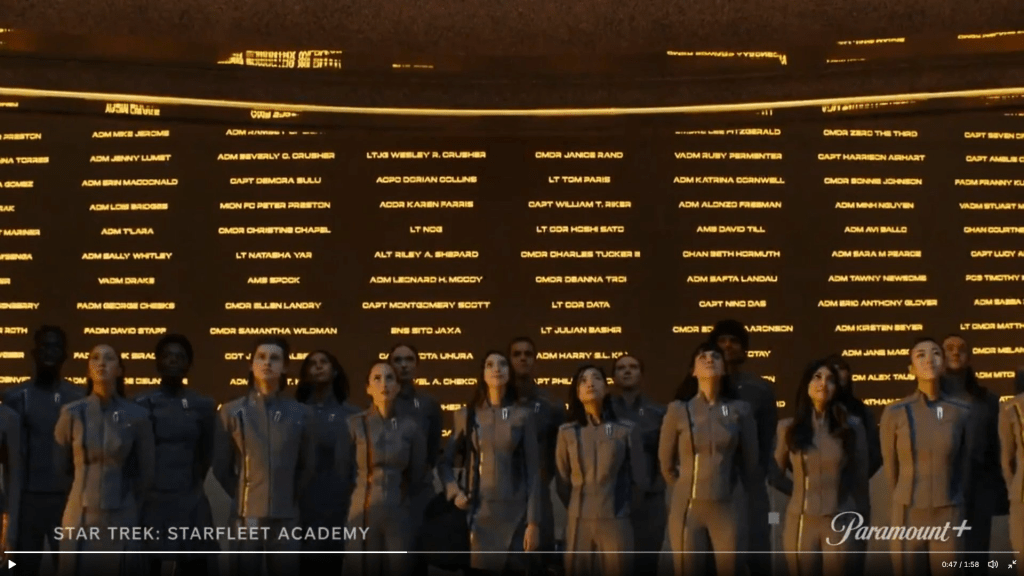

But the trailer that I’ve seen the most online chatter about had nothing to do with plot reveals, special effects, or the performances of the actors involved. No, the most talked-about trailer this year seems to have been the teaser for the upcoming Star Trek: Starfleet Academy series on Paramount+. Here’s all you need to know: Starfleet Academy takes place further along in the timeline than most of the Trek shows and movies that we’ve grown to love over the past six decades. In this time period, the Federation almost collapsed due to certain catastrophic events and it’s now in a rebuilding stage. This series is about the rebirth of the Academy, and the scene that has everybody talking is one in which we catch a glimpse of what appears to be some sort of Wall of Honor, adorned with the names of legendary Starfleet personnel. Ambassador Spock. Admiral Jean-Luc Picard. Lieutenant Nog. There are names on this wall from virtually every iteration of Star Trek to date. This one scene has had people freeze-framing it more than any single scene since Fast Times at Ridgemont High, trying to read all the names on the board to see who amongst our favorite Star Trek characters made the cut. I seriously doubt that this wall will have any great significance to the plot of the series, but it’s a fun Easter Egg for those of us who have loved Trek for so many years.

In one of the (many) online discussions I’ve seen about this scene, though, there was one dissenting voice that I found perplexing. This person, whom I am paraphrasing, basically expressed irritation that all of the characters that we’ve watched over the years turned out to be so remarkable. Statistically, they seem to think, not EVERY character should turn out to be some kind of legendary figure.

This person has got it completely backwards.

My reply was simply this: “It’s not that every character we watch has turned out to be remarkable. It’s that we are only watching them in the first place BECAUSE they are remarkable.”

This is one of those times where I engage in a discussion online over something that I always thought was blindingly obvious, only to learn that not everybody sees it my way (also known as the correct way). There are hundreds, maybe thousands of ships in Starfleet. Of course not EVERY ship and EVERY crew is going to turn out to be the one that makes it into the history books. But doesn’t it stand to reason that those boring, mundane crews are simply not the ones that we get to hear the stories about? In other words, the histories of the Enterprises, Voyager, or station Deep Space Nine aren’t remarkable because those are the crews we follow. We follow them because they ARE the remarkable crews.

This is the case with fiction across the board. We aren’t tuning in to a movie or a TV show to watch the adventures of some average, everyday schlub. There are exceptions, of course – “slice of life” dramas and comedies do just this, and sometimes they do it very well. But in the case of an adventure series like Star Trek, you’re following the exploits of the characters that make history. They even tried to subvert this expectation with the animated series Star Trek: Lower Decks. The idea behind it was that we were going to FINALLY follow the adventures of an unimportant crew on an unimportant ship. And what happened? It turned out that they weren’t all that unimportant after all, and if anything, Lower Decks winds up reading as the origin story for the next one of these legendary crews.

Suspension of disbelief is an important aspect of enjoying fiction. There has to be a willingness, as a member of the audience, to accept certain things that you are aware may defy reality. In the case of speculative fiction – sci-fi, fantasy, and certain types of horror – that means that you have to maybe ignore certain laws of physics. Yeah, Einstein said that we can’t go faster than light, but if we didn’t find a way to do it then there would be no Star Trek, so I’m gonna let that one slide. Quantum mechanics says that the way time travel works in Back to the Future is utterly impossible, but until quantum mechanics can give me something as awesome as Alan Silvestri’s score, quantum mechanics can bite me. Is there really such a thing as a creature that can hide inside your dreams and attack you? Probably not, but A Nightmare on Elm Street wouldn’t be nearly as scary without him.

Those are the big things, though, and when it comes to suspension of disbelief, people are oddly MORE accepting of the big things. What about the little things? There’s an old saying that in real life we expect the unexpected, but in fiction we don’t stand for it. Major, life-changing events have to be the REASON for a story, not something that simply happens IN the story. Think of it this way: if a character in a movie wins the lottery, that usually happens at the beginning of the movie, and the rest of the story is about what happens to them as a result. But if a character in a movie is in some sort of desperate situation – maybe he’s spent half the movie running from the mob because he owes them a fortune and they’re gonna break his kneecaps – and THEN he wins the lottery, the audience considers it a cheat. The suspension of disbelief breaks down here, even though the odds of a person winning the lottery are – mathematically speaking – exactly the same at the beginning of a story as they would be at any other point. I’ll accept a lottery win as the inciting incident, but if a random lottery win is what saves the day, that’s a modern deus ex machina, the “god in the machine.” It comes from those times in Greek drama where a character would be rescued by – literally – one of the gods intervening to get them out of a jam, and even back then it pissed off the ancient Greeks so much that they invented machinery just so they would have a term to use to complain about it.

It doesn’t have to just be good things either – tragedy can break your suspension of disbelief too. There are a lot of tearjerkers about somebody battling an incurable disease, and we’re okay with that, because that’s what the story is about. On the other hand, if somebody spontaneously develops such a disease in the middle of a story without any prior warning, audiences will consider it cop-out. Why? In real life, people can get sick at any time, so why NOT when it’s convenient for the plot?

Because “convenient” is enough to break the reality of the fiction.

The rule is basically this: major life-changing events (either good or bad) either have to happen at the beginning of the story or be the consequences of the actions in the story, but they cannot happen randomly in the middle or end of the story or the audience won’t stand for it.

The one exception here – and even this one is iffy sometimes – is when you’ve got a long-running serialized story like a television or comic book series. When you’re following characters for years at a time, eventually a random event will occur, and the audience will be a bit more accepting of it. For example, the death of Marshall’s father in the series How I Met Your Mother came out of nowhere, but that episode is considered one of the most powerful, emotionally-resonant moments of the entire series. It’s something that hits the audience hard, forcing us to process the grief and pain of the character along with him. (The story goes that actor Jason Siegel didn’t know what the end of that episode was going to be until they filmed it, so when Allyson Hannigan delivers her line, telling him that his father died, his response is entirely genuine and his final line was a perfect ad-lib: “I’m not ready for this.)

In a comedy, suspension of disbelief is allowed to go even farther. In a farce like The Naked Gun, for example, things routinely happen that make it feel more like you’re watching a cartoon than a live-action film, and the audience is perfectly satisfied. Nobody complained in the end of Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles when Hedley Lamarr bought a ticket to a movie theater showing…Blazing Saddles. And Mystery Science Theater 3000 even wove the concept of Suspension of Disbelief into its THEME SONG: “If you’re wondering how he eats and breathes and other science facts, just repeat to yourself, ‘It’s just a show, I should really just relax’.”

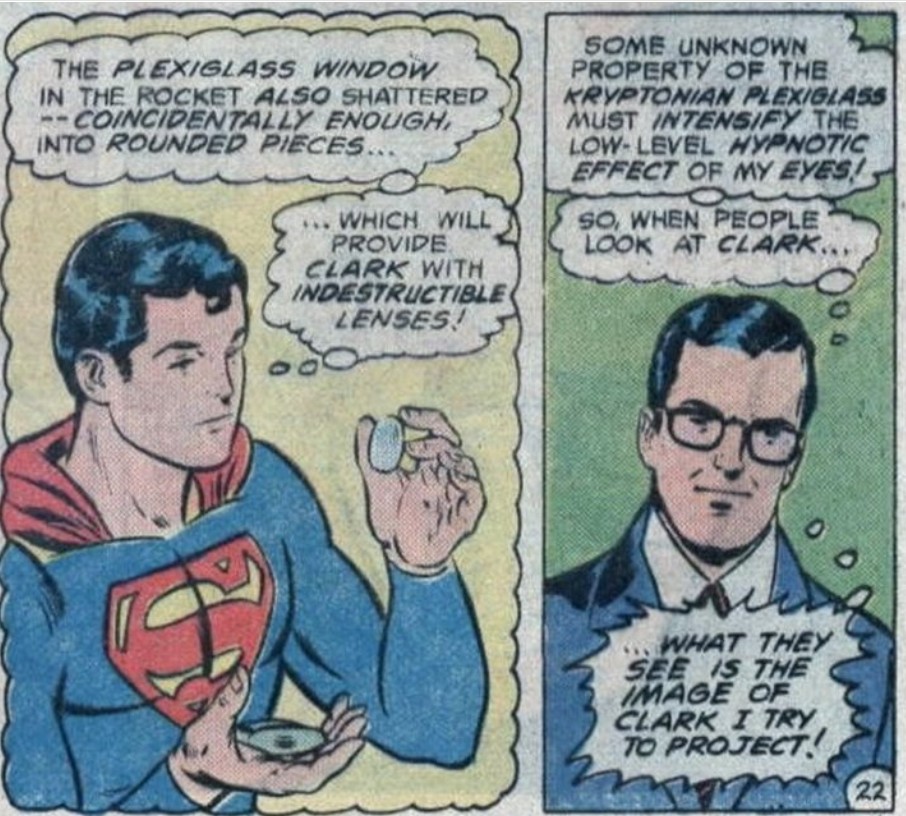

On the other hand, if that disbelief is suspended too long, there’s a temptation to try to work things into the story to justify the extraordinary. For instance, for decades there was a running commentary about how Clark Kent’s glasses wouldn’t fool anybody and that everyone would quickly realize he’s Superman. Eventually, the writers felt that it needed to be addressed to maintain the suspension of disbelief. Some writers said that he slouches as “Clark,” or changes his voice and mannerisms. Sometimes they actually have him attend acting classes specifically to learn how to do this. Sometimes the lenses are made out of special glass (usually from the ship that brought him from Krypton) that either changes the color of his eyes or – in the most extreme case – has a hypnotic effect on the people who look at him, making them see a different face. James Gunn even alluded to that in his movie, although a lot of people thought it was just a typical Gunnian joke, not realizing it was a legitimate piece of comic book lore.

We don’t read or watch fiction – for the most part – looking for ordinary things. We want to follow the adventures of extraordinary people or, at the very least, ordinary people in extraordinary situations. Stephen King fans (this is me raising my hand in the back of the room) will tell you that’s his great strength: the ability to create a realistic character and then show how they respond to circumstances that no realistic character could possibly have prepared themself for. And to be fair, a certain amount of analysis and nit-picking is acceptable when you’re discussing great works of fiction (or even awful works of fiction).

But eventually, when somebody online says something like, “Why don’t people in Gotham City ever realize that Bruce Wayne is the only one with the money to be Batman?” The proper response is simply, “Because the story wouldn’t work otherwise, so just get over it.”

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His most recent writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, volume one of which is now available on Amazon. You can subscribe to his newsletter by clicking right here. He’s also started putting his LitReel videos on TikTok. He, too, would like to wear hypno-glasses, but in his case he would just use it to make his students see him as Yoda.