Two years ago, in a move that made pundits across the world scratch their heads and say, “Well how the hell did that happen?”, Netflix purchased the Roald Dahl Story Company. This trust, of course, is responsible for the works of the creator of such things as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, and that one short story about the snake. At the time, Netflix announced that this acquisition would lead to the development of their own shared universe, copying the Marvel Method just like everybody else has been trying to do for the last decade. So far, though, we haven’t seen a ton of stuff that feels like it’s part of that world. We’ve gotten a film version of the theatrical Matilda: The Musical, and later this year they’re going to release Wonka, an origin story for a character that Tim Burton definitively proved in his film version has absolutely no need for an origin story, but not much else.

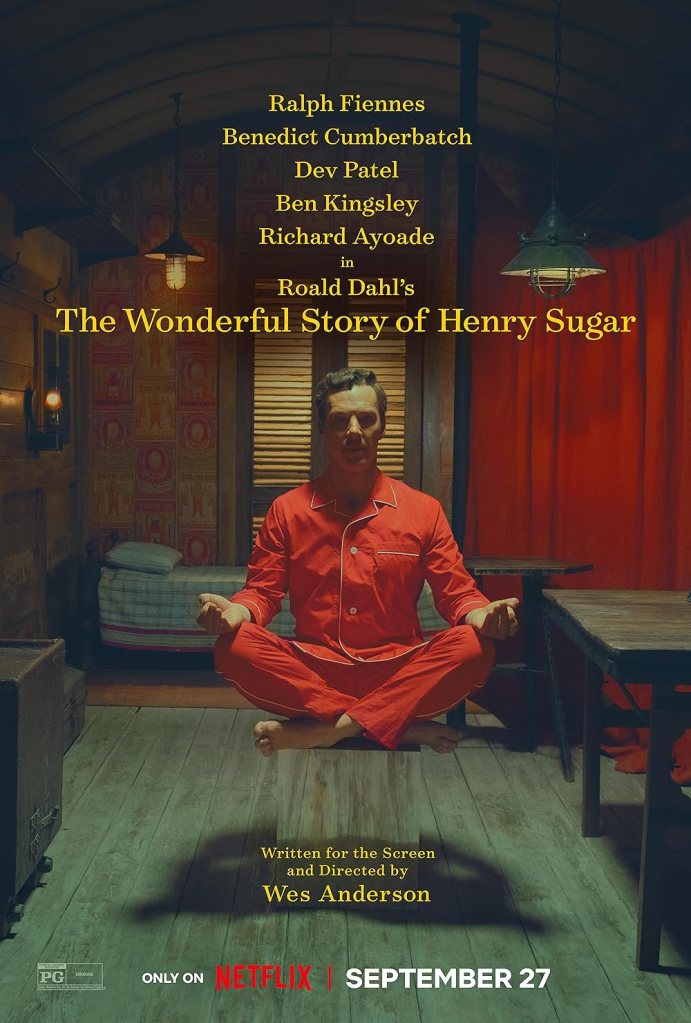

Earlier this week, though, Netflix surprised us all by dropping The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, a film based on one of Dahl’s short stories. The movie is directed by Wes Anderson (who also directed the Dahl adaptation The Fantastic Mr. Fox back in 2009) and stars Benedict Cumberbatch as a compulsive gambler who finds a secret to a mysterious power that could potentially make him the wealthiest man in the world. Despite a premise that could easily go very, very dark, the film (and the story it is based on) is remarkably sweet and optimistic, lacking the cynicism that so often creeps in when modern filmmakers attempt to adapt a classic piece of literature that didn’t have a lot of cynicism in the first place. It’s very much a Wes Anderson film, carrying on an odd obsession with films mimicking stage plays that we also saw in his recent feature Asteroid City. The sets of the film are flown in and out in full view of the cameras, the majority of dialogue is spoken directly to the viewer as if the actors were narrating a play, and even visual effects are done in a dime-and-nickel fashion, such as making a character “levitate” by having the actor sit on a box painted to match the set behind him. It’s weird and bizarre and utterly delightful.

It’s also only 39 minutes long.

Although originally presumed to be a feature film when announced, Anderson quickly corrected people, saying that it’s actually the first of four shorts he is making adapting various Dahl stories for Netflix. True, 39 minutes is longer than most of us think of as a “short” film (the classic Looney Tunes shorts were usually in the seven-minute range, and even the Three Stooges rarely broke 20), but it’s certainly not long enough to qualify as a feature film, which has to hit at least 80 minutes to be worthy of consideration. We’ve all seen poorly-made films that pad out their running time to hit that mark, in some extreme cases even running the credits at an excruciatingly slow pace just to cross that 80-minute finish line. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences officially defines a short film as running no longer than 40 minutes, including credits, so Anderson got in just under the wire if he’s looking for Oscar consideration, which I’m sure Netflix would LOVE.

The odd thing is, as recently as 10 years ago, a film of this nature would have struggled to find a home. Since the end of the era of true theatrical shorts (an era I long for, an era I would dearly love to see return), a lot of theaters never would have run one as long as Henry Sugar. The only way such a film would get any theatrical showing would be in a showcase of short films, which wouldn’t be in wide release, or as part of an anthology of shorts, which historically have not performed all that well. As far as a TV release, it could possibly be aired as a “special,” but would certainly be cut up to add commercial breaks, and possibly even cut down to make room for more commercials. At any rate, stopping a film of this nature to show an ad for Tide Pods would be absolutely gutting to the flow and pace, and make for a far less enjoyable experience than watching it all in one go, like a stage play, as Anderson intended.

Netflix is honestly the perfect home for a film of this nature, and it’s not just this one. Although I have many issues and concerns with the streaming culture that we all live in nowadays, one of the main advantages I think it has given us is the freedom to make a film as long or as short as necessary to tell the story.

Many people get twitchy at the prospect of watching a movie that’s “too long” (these people usually define that as anything north of 90 minutes). I don’t know if it’s a short attention span or a bladder that just can’t wait, but once they see that runtime creep towards 130, 140 or higher, there are lots of people who would rather skip the whole experience. I have no problem with a long movie – most of my favorites would fall into this category, in fact – so long as the story justifies the length. I hear people complain about the length of the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings films, for example, but I’ve never been given a satisfactory answer when I ask them what they think could be cut for time without damaging the story. This is why miniseries became so popular in the 80s and 90s, giving more time to adapt a novel that couldn’t fit into a two-hour theatrical experience. It’s why full television series are now being based on books, things like Game of Thrones or Outlander, stories that just flat-out couldn’t squeeze into a movie. And this is, for the most part, a positive thing.

The opposite is also true, however. If stretching out a movie longer than it should be is dull, padding a short movie to make it feature length is deadly. As an avid and enthusiastic moviegoer, I’ve probably seen hundreds of films in theaters over the course of my life, and one of the few times I can remember ever actually falling asleep was in the 2001 film Imposter. (Side note: pound for pound, boring movies are even worse than bad movies. A boring action movie is simply unforgivable.) The film was about an alien race using androids as hidden human bombs trying to attack Earth, and Gary Sinese’s desperate attempt to prove he was not one of these living bombs. It’s a good concept, and Sinese is a great actor, so it’s almost criminal how unbearably dull that film is. I was baffled as to how such an excruciatingly boring movie could be made…until I found out that it was originally made as a short film, part of an anthology of science fiction stories, and it was then expanded out to feature length. If you carved out the parts of the movie that were part of the original short, you may have had a good, taut sci-fi thriller, but by adding additional unnecessary scenes to essentially triple the length of the film, it’s as entertaining as watching Hollywood accountants try to lie about how much money a movie made.

Telling a short story is an art that requires different skills than longform stories. The tools are the same, but you wield them differently. A long story can spend time developing plot AND character AND setting AND mood AND theme, whereas shorter works often have to settle for focusing on just one or two of the elements. When it’s done well, it can be a masterpiece. But even those masterpieces can be damaged if you go back and start adding things that don’t belong. It’s like taking a VW Beetle, cutting it in half, and inserting a segment from a stretch limousine. You’ve taken two perfectly good automobiles and turned them into an abomination that doesn’t belong on the road.

It’s hard to make a feature film out of a short story, because by definition, those stories are intended to be short. It CAN be done very well, of course. Several of Stephen King’s short stories have been made into solid features – 1408, the original Children of the Corn, and by all accounts the new adaptation of The Boogeyman (I haven’t seen it yet but I hear very good things about it) each took a brief story and expanded it into features that are engaging and entertaining. On the other hand, sometimes the filmmakers can’t quite build a feature out of a short story, giving us lesser offerings like The Mangler. And sometimes they just try to trade on the name and make no effort at adapting the story at all, and here I of course am referring to Lawnmower Man.

Children’s books are frequent victims of this problem. Books for kids – especially picture books for young children – may only have enough story to last 20 minutes or so. But if you want a theatrical release, that just ain’t long enough, and you have to start inventing stuff out of whole cloth. Sometimes it works. Dreamworks took two short children’s books – Shrek and How to Train Your Dragon – and turned them into flourishing franchises by using the book more as inspiration than a blueprint. On the other hand, look at the awful efforts that the late Dr. Seuss has been subjected to. There have been two separate feature films based on How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and both of them suffer from inflation and unnecessary backstory. What Chuck Jones nailed in 26 minutes, Ron Howard and Jim Carrey puffed out to a painful 104.

The less said about The Cat in the Hat, the better.

The streaming world has changed this paradigm, though. Previously, there were only two “acceptable” outlets for a film: television or theatrical release. Sure, direct-to-video was a thing, but those usually tried to emulate theatrical movies in form, either to fool people or to maintain an air of respectability. But whether you were making a project for theaters or TV, either way you were chained by scheduling in one way or another. In traditional ad-supported television, almost anything you make has to fit perfectly into a strict schedule of 30 or 60-minute blocks, minus an exact amount of time for commercials. Deviation is not tolerated, because we have to fit in a very specific amount of advertising time. Even premium cable channels, which are not beholden to advertisers, often use that 30-minute grid for scheduling, then pad out the remaining time with promos for their own networks so they can start the next movie or TV show on the hour.

Theatrical movies have a little more wiggle room – there isn’t a hard and fast rule that a movie has to be EXACTLY 90 minutes – but there are still parameters that have to be adhered to. If a movie is less than 80 minutes, theater chains usually won’t run it, as filmgoers will be disappointed at spending $127 on tickets, candy, and soda to take their family out to see something that’s over in under an hour and a half. On the other hand, the longer a movie is, the fewer times a day it can be shown, meaning fewer tickets sold, which again makes theater owners hesitate unless it’s a film they feel is a guaranteed blockbuster. Marvel movies can get away with a longer runtime because they historically bring big box office. Oscar bait dramas can do so as well, particularly if they come from a major studio. But if you’ve got a no-name director, no big stars, and aren’t tied to a recognizable IP, showing up at AMC with your 3-hour long epic about the Battle of New Orleans probably isn’t going to fly.

But on Netflix, Prime Video, or any of the other bajillion streaming services, neither of these factors need to be considered. A viewer doesn’t have to be in front of their TV at 8 o’clock because that’s when their favorite show airs anymore. They don’t have to show up at the theater at 6:45 to get settled in before the previews roll at 7, and they don’t have to worry about running out in the middle of the film to feed the parking meter because Kumquat Warriors 7: The Kumquatening is a longer movie than the previous three combined. In a streaming world there is no reason to make a movie or TV show any longer or shorter than is necessary to effectively tell the story.

Streaming series have been running with this a lot. Although they still kinda aim for the old TV paradigm of half-hour comedies and one-hour dramas, they aren’t strict about it. If an episode takes 37 minutes instead of 30, no big deal. If it only reaches 48 minutes instead of 60, we can let it slide. The series The Orville, for its most recent season, jumped from the Fox broadcast network to the Hulu streaming service, and once they were no longer locked in to 42 minutes of show plus 18 for commercials, they delivered an entire season of episodes that went well over an hour. Several of them are long enough that they could have been released as theatrical films. And for the most part, they were very entertaining and compelling, using the freedom of the format to great effect.

And while movies can have the freedom to get longer, things like Henry Sugar are demonstrating that the real freedom is to get shorter. In 2020, in the midst of the Covid lockdowns, Rob Savage made a horror film called Host. The film used the lockdown to great effect, telling a story of a group of friends on a zoom meeting that accidentally summon a dangerous spirit. Shudder picked the movie up and it became a cult hit, despite the fact that the running time is only 57 minutes. This is a film that never could have found a theatrical release without adding a half-hour of fluff, but the streaming world allowed Savage to just tell his story as he saw fit, and that gave it wings that it wouldn’t have had with any traditional distribution model.

There are a lot of things about the streaming world that concern me – I’ve mentioned many of them before. But if there’s one thing that is definitely positive about it, it’s the fact that time constraints are largely a thing of the past. The freedom to tell a story in the most effective way without trying to adhere to largely arbitrary rules of running time has already produced some really great content. The important thing is that a filmmaker is allowed to include whatever is necessary but not forced to add things that don’t matter, and that path (in the hands of a skilled crew) will make better movies. If there’s nothing else we can learn, it’s that when it comes to telling a good story, size isn’t what matters at all.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His current writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, a new episode of which is available every Wednesday on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform. He‘s hoping that this season’s finale of Lego Masters has a seven-hour streaming cut.