Just a few weeks ago, I wrote about experimental storytelling, looking for movies, books, or other media that found a new, innovative way to tell a story. As tends to happen, shortly after I wrote that column, I stumbled across something that absolutely would have been under discussion had I been aware of it at the time. It’s kind of like getting home from the supermarket and realizing you forgot an essential ingredient for the cake you’re making for my wife’s birthday, and I better haul ass back over there before she gets home. As a purely hypothetical example.

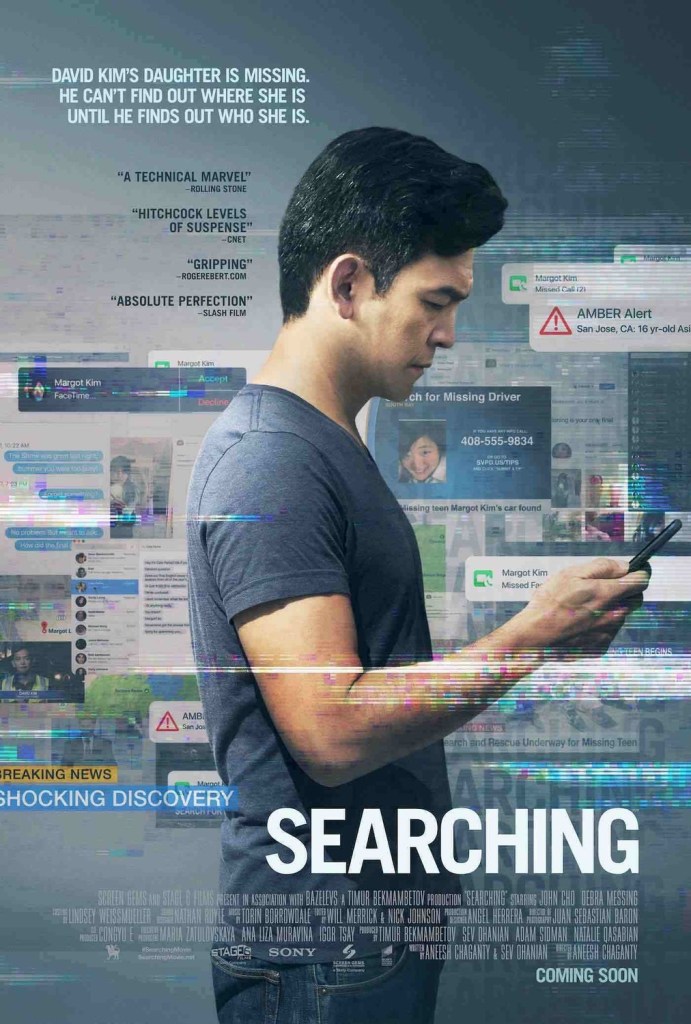

Last week I watched Searching, a 2018 film starring John Cho and Debra Messing, directed by Aneesh Chaganty, and written by Chaganty and Sev Ohanian. The film is a mystery and thriller about a father (Cho) whose teenage daughter (Michelle La) disappears, and the only clues he can find to her disappearance are those he can plumb from the depths of her laptop computer. Fortunately, despite the setup, they resisted the urge to do a Taken knock-off. The interesting thing about Searching is that the entire story is told through the screens of phones and computers. All you – as the audience – ever see is what appears on that screen.

This isn’t the first movie to use that conceit, of course. I can think of at least three movies from the past decade told via computer screens: Open Windows (2014), Unfriended (2014), and Host (2020). Those three movies all have far more in common with each other than Searching, though. First of all, those are all horror movies. Second, the things we see on the screen in those films are mostly open Windows for Skype, Zoom, or other such teleconferencing aps. Although there is some playing with the format, in many ways they’re an evolution of the found footage craze.

Searching is different. We still see the actors on screen fairly frequently (there’s a lot of Facetime happening in this movie, plus security footage, TV news broadcasts, and other justifications to put them on camera), but that’s not the usually compelling part of the film. The interesting thing is seeing Cho’s character using the information on his daughter’s laptop to track her down: old vlogs, emails, and different social media and other accounts that, over the course of the film, paint a picture of the girl he raised. It helps the audience to understand her, and from a storytelling standpoint, it also helps Cho to realize he no longer really knows his daughter the way he believed he did. The mystery is good. It’s compelling. But the format is what I really want to talk about today.

Although some of those earlier movies I mentioned do some of the things we see in Searching, it’s the way the movie uses the digital space that makes it stand out. We’re watching this mystery solved as the different elements are revealed to Cho. It’s not exactly realtime, there are jumps and lapses and the whole film takes place over the course of about a week, but it almost feels like realtime. We get to see things from Cho’s perspective – a text message he types then deletes unsent, for example – that reveal things about the character. In a conventional movie, this is all the stuff that happens before the scene where the detective shows up and says, “I found some information about your daughter, Mr. Kim.” In this movie, that stuff is the story. You wouldn’t think a scene focused on someone trying to change their Gmail password would be tense and compelling, but I’ll be damned if Chaganty didn’t make it work.

At least part of it, I think, is that it feels so relatable. We’ve all used social media, we’ve all done Google searches…we actually know what it is that Cho’s character is doing throughout the film, so we’re anxious to see the result. Occasionally, our familiarity with the language of computers clues us in to information that may not be immediately obvious to the detective himself if he’s not looking at the right area of the screen. And most importantly, in this digital age we live in, it seems very possible that REAL mysteries are solved this way now. All of this together made it a film that was fun to watch.

This raised a question, though. Did I like Searching because it was a good story, or did I like it just because it was an original gimmick? There are a lot of storytelling gimmicks that are cool the first time you see them, but get stale quickly. 3-D is the best example I can think of. Sure, there’s a visceral thrill to seeing a 3-D movie…or at least, there was the first 500 times it was done. But I have yet to see a movie in which 3-D actually improved the story, and that’s what it will take to convert me. I call it the “Wizard of Oz” moment. That was the movie that demonstrated that color could be used to make a story better than it would be in black and white. I haven’t seen 3-D’s Wizard of Oz moment.

And that’s what I needed to answer about the way Searching was told. Was this “on-screen” narrative technique something that could add new elements to the vocabulary of cinema, or was it just a one-off trick that would grow stale if repeated? There’s no way to answer that without trying it again.

And so they did.

Earlier this year we got Missing, a sort-of sequel to Searching written and directed by Nicholas D. Johnson and Will Merrick. I say “sort of” because, although it continues the use of the on-screen narrative, the stories really aren’t connected in any way. It’s a new cast, a new mystery, and except for a few times where the characters reference a Netflix “true crime” series they watch that (in-universe) depicts the events of the first movie, there’s no connection between the two whatsoever. In Missing we follow the efforts of a daughter (Storm Reid) trying to track down her mother (Mia Long), who never comes home from a vacation in Columbia with her boyfriend (the terribly-underutilized Ken Leung).

Okay, so it’s another missing person movie. But complaining about that would be like going to see a Chucky movie and complaining that they’re using that talking doll again. It’s just the conceit of the franchise. The question is whether the sequel can tell a satisfying story, now that the audience has seen and is used to the trick of following the events on the computer screen. And from my perspective, at least, the answer was yes.

Except for the missing person angle, Missing really doesn’t borrow from Searching in the plot department. First of all, using the teenager as the protagonist (and, for purposes of the story, the main detective) makes us approach the story in a different way. Her resources weren’t quite as vast as those of an adult, and she was less likely than an adult may be to sit back and wait for the police to take care of matters happening in another country. This leads to an unlikely friendship between Reid’s character and Joaquim de Almeida, who she contacts using an app to hire someone for minor chores and turns him into her man on the ground in the country where her mother disappeared, but she can’t follow. The way the two of them work together from thousands of miles apart to unlock clues is entertaining and leads to some touching moments.

There are, admittedly, a few times where it seems like the filmmakers are aping Searching a little too closely, but they wind up using those as opportunities for plot twists and surprises. Without getting into spoiler territory for either film, I feel like anyone who has seen Searching will have certain expectations that make it almost impossible to identify the villain of Missing until the reveal. Storm Reid’s character and circumstances are different enough from those of John Cho that it doesn’t feel any more derivative than any other two missing person movies you might watch.

Like all sequels, there is an imperative to escalate the story. The scope is broader – the movie goes international this time – and the climax is told more through security camera footage, making it a bit more traditionally “cinematic” than the first film. Even then, though, the story manages to use the concept and the characters to their advantage, providing a key piece of information that would have been a little dull if they tried the same trick in a conventional movie. The important thing here is that, once again, the style worked. And if it works twice, that’s a good indicator that it may not just be a gimmick, it may be a legitimately new way to tell a story.

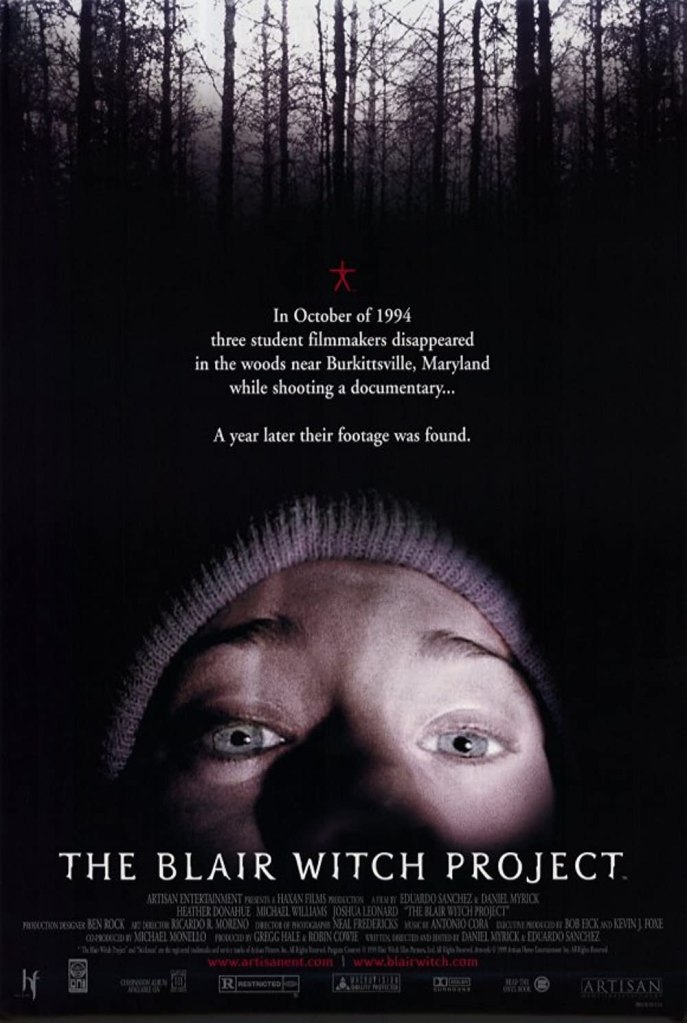

I think, to me at least, that’s the difference between a gimmick and a new storytelling technique: repeatability. The aforementioned found footage movies are a perfect example. The Blair Witch Project wasn’t the first found footage movie, but it catapulted the concept into the mainstream. Several years later Paranormal Activity brought it back. Both of them inspired dozens of imitators that were found wanting, but that doesn’t mean found footage itself can’t work. It just needs to be applied to the right project. Although there have been found footage films in numerous genres, the most popular and successful examples have usually been horror movies, which lend themselves to that format very well. Similarly, this “on-screen” narrative works very well for a mystery, because what you’re really watching is somebody trying to piece together a puzzle. Do I want to watch a thousand crappy mystery movies about someone using their kid’s laptop to track them down? No. But now that the format is out there and proven, I am very interested to see what other kinds of stories can be told this way.

And that doesn’t just mean in movies, either. The more I think about this setup, the more I think it could make for a very compelling video game. It would be a sort of digital equivalent to an escape room. In fact, it reminded me of the last time I played an escape room on a family vacation to Hot Springs. In the game, we used a deceased relative’s computer to sift through documents and emails to figure out where in the room to look for clues. For my nieces and nephew, the high point of the game was when I retrieved a hidden clue tied to a pair of ancient granny panties from an air duct, but for me I really enjoyed the way the game was put together, which I think would translate digitally very well.

I can imagine a game where the player takes the role of the detective, similar to John Cho and Storm Reid in their respective films, and has to crack some sort of mystery. As the game begins you are presented with a laptop interface with a video clip that you’re instructed to play to set up the story, then you use the information on the computer to crack the case. This would, admittedly, be a pretty substantial undertaking. The game would have to come preloaded with documents, files, video and audio clips, emails, social media platforms…it’d be a task to plan the whole thing out and produce all of the clues necessary, not to mention figure out a way to guide the player through it in a way that creates a satisfying experience, but I honestly think it would be a lot of fun.

I should mention here that I am not a gamer, I haven’t owned a video game console since my parents got a Sega Genesis I shared with my brother and sister, so it’s entirely possible that what I just described already exists. If it does, I don’t know about it, but I would be very interested if you could point me in that direction. In fact, I imagine at least three of you have already posted an angry response to point out my ignorance of some game that fits the pattern exactly. (“Clearly you’ve never played Leisure Suit Larry 19: Larry’s Hard Drive.”) If so, just send me a gentle notification, will you? Especially if it’s a mobile game.

I’m happy to find something that I hadn’t encountered before. Storytelling is one of my favorite things in the world (it comes #3 after my family and the return of the McRib), so any time someone can show me a way to do it that I haven’t seen before, I’m fascinated. I’m just crossing my fingers that the storytellers who see Searching and Missing and think “I can do that” learn the right lessons instead of just hitting copy and paste.

Blake M. Petit is a writer, teacher, and dad from Ama, Louisiana. His current writing project is the superhero adventure series Other People’s Heroes: Little Stars, a new episode of which is available every Wednesday on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform. It’s kind of amazing how much better the security was on John Cho’s kid’s laptop than in the entire Louisiana Office of Motor Vehicles.